Genetic analysis has found that the fatty tissues in the heads of toothed whales used for echolocation evolved from what were once their skull muscles and their jaws' bone marrow.

Toothed whales are the 73 species of cetacean that include dolphins, porpoises and sperm and beaked whales. They use sound to communicate, navigate and hunt, and the new research by scientists at Hokkaido University in Japan involved investigating DNA sequences of genes expressed in this fatty tissue, called “acoustic fat bodies”.

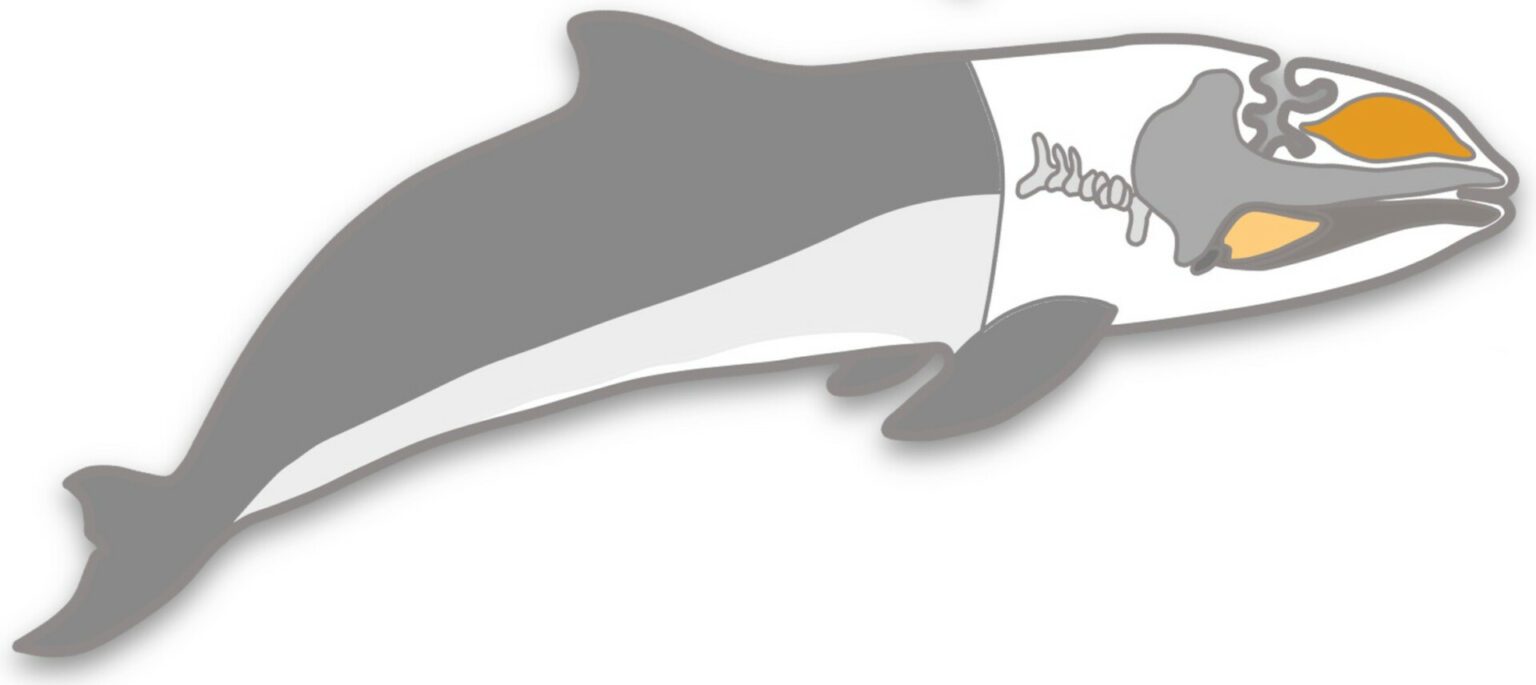

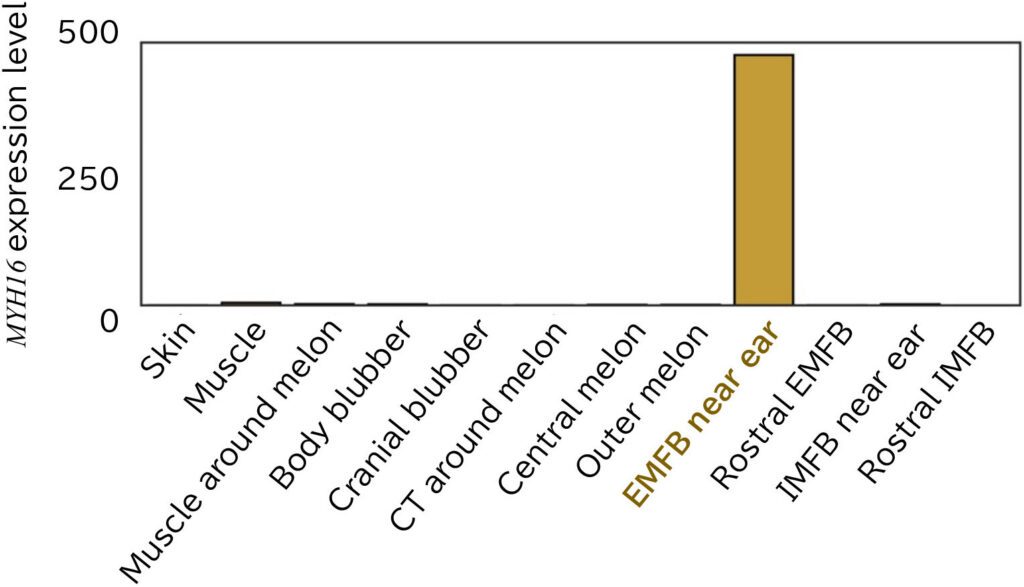

The scientists measured gene expression in harbour porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) and Pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens). The acoustic fat bodies are found in the melon in the forehead, extramandibular fat bodies (EMFB) alongside the jawbone, and intramandibular fat bodies (IMFB) within the jawbone.

Although the tissues’ evolution was essential for sound use such as echolocation, little had been known about where they came from. “Toothed whales have undergone significant degenerations and adaptations to their aquatic lifestyle,” says Hayate Takeuchi, a PhD student in the university’s Hayakawa Lab and first author of the study.

One adaptation meant the partial loss of the whales’ sense of smell and taste, which was swapped over time for the echolocation that enabled them to navigate efficiently under water.

The researchers found that genes normally associated with muscle function and development were active in the melon and EMFBs. There was also evidence of an evolutionary connection between the extramandibular fat and the masseter muscle, which in humans connects the lower jawbone to the cheekbones and is key to the act of chewing.

“This study has revealed that the evolutionary trade-off of masticatory muscles for the EMFB – between auditory and feeding ecology – was crucial in the aquatic adaptation of toothed whales,” said Assistant Prof Takashi Hayakawa of the Faculty of Environmental Earth Science, who led the study.

“It was part of the evolutionary shift away from chewing to simply swallowing food, which meant the chewing muscles were no longer needed.”

Analysis of gene expression in the intramandibular fat also detected gene activity related to immune functions.

The samples used in the study were collected by the wildlife rescue service Stranding Network Hokkaido (SNH). “Long-term communication with local people and communities in Hokkaido has enabled researchers to conduct various studies of whale biology, including our surprising findings,” said SNH director Prof Takashi Fritz Matsuishi.

Those findings have just been published in the journal Gene.

Also read: Secret’s out: how whales sing without drowning, Sperm whales: The enigmatic giants of the deep, BDMLR ready as dolphin strands in Cornwall, Monty Halls rescues stranded dolphin