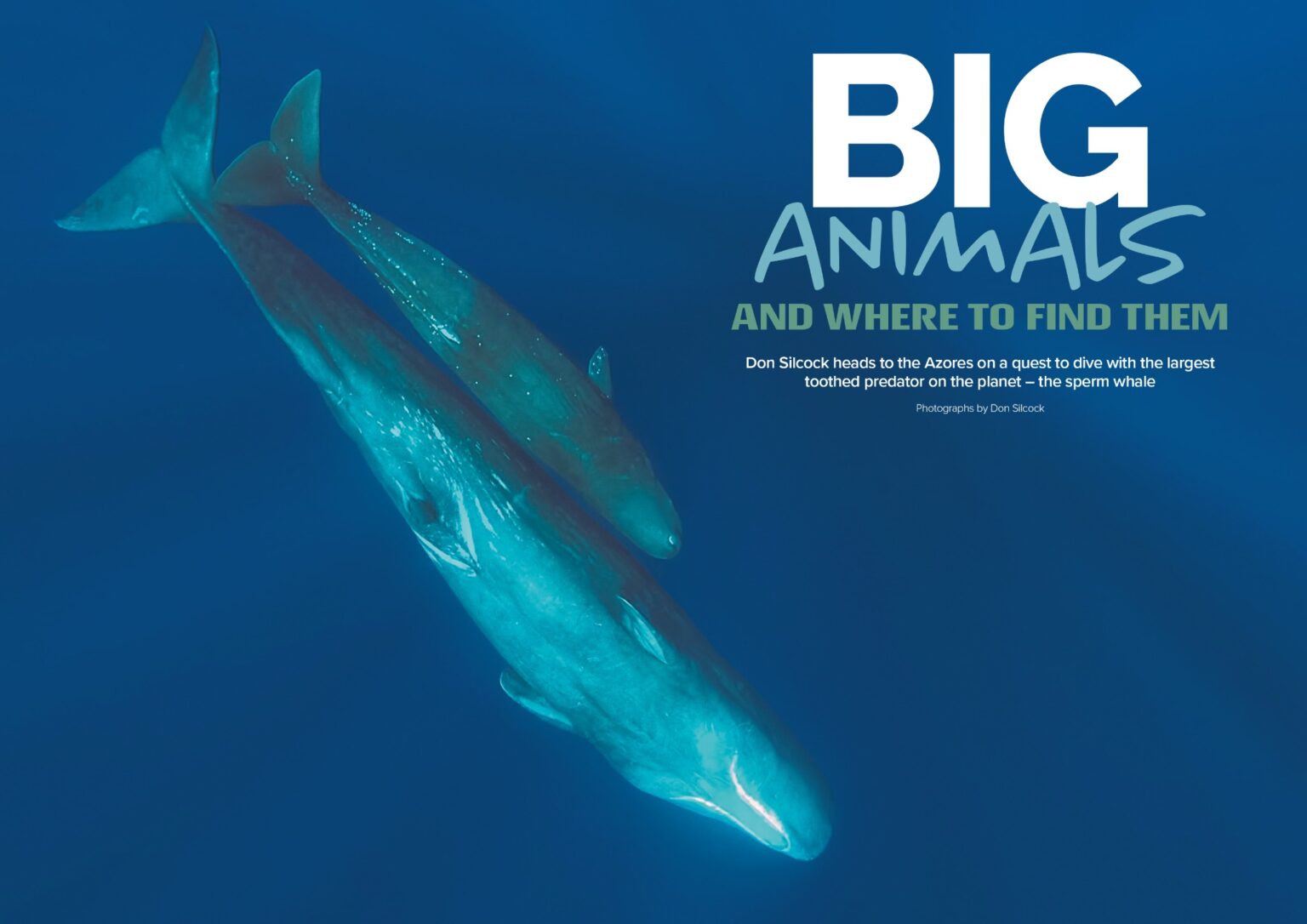

Don Silcock heads to the Azores on a quest to dive with the largest toothed predator on the planet – the sperm whale

Photographs by Don Silcock

Did you know?

Sperm whales are the largest of the toothed whales and have one of the widest global distributions of any marine mammal species. They are found in all deep oceans, from the equator to the edge of the pack ice in the Arctic and Antarctic!

Sperm whales are the world's largest toothed predators, with the biggest males reaching almost 18 meters in length and weighing approximately 57 tonnes. Females, on the other hand, max out at around 12 meters and 17 tonnes.

These truly pelagic and peculiar-looking creatures can be found in various locations, from the warm waters of the Caribbean to the icy ones of Greenland and Norway. However, they are typically found in areas with deep waters nearby, as that is where they hunt their primary prey—the fearsome giant squid. A mature male sperm whale can consume up to one tonne of these squid per day.

Their distinctive shape is derived from their enormous, block-shaped head, which accounts for almost one-third of their total length. This head is filled with a semi-fluid, waxy substance that led to their name. When freshly drained, it resembles and smells a bit like raw milk, which led the whalers who hunted them to believe it was their semen. Thus, the substance was named ‘spermaceti' (Latin for ‘whale sperm'), and the whales became forever known as ‘sperm whales.'

Marine scientists now believe that spermaceti's primary function is to enhance the whales' sonar echolocation, which they use to locate giant squid in the vast depths of the ocean. Spermaceti transmits sound extremely fast, turning the whale's massive head into a powerful telegraph machine, enabling the whale to detect both the squid's motion and its position.

Whaling and Spermaceti's Value

The head of a sperm whale can contain up to 1,900 liters of spermaceti, which was highly sought after during the 17th and 18th centuries. Processed spermaceti forms brilliant white crystals that are hard but oily to the touch, odorless, and tasteless. It became an essential ingredient in cosmetics, leatherworking, and ointments. Moreover, expensive candles made from spermaceti burned brightly without producing smoke, making them highly popular in European upper-class homes before the advent of electricity.

The pursuit of this valuable substance led to the accumulation of many whaling fortunes. Unfortunately, it also resulted in the decimation of the global sperm whale population by almost 70%.

The Azores: A Haven for Sperm Whales

Due to their pelagic nature, in-water encounters with sperm whales are rare. To increase the chances of such an encounter, one must venture to locations where these creatures are known to aggregate at certain times of the year.

The islands of Dominica in the eastern Caribbean are perhaps the most reliable location for such encounters. However, encounters in remote places like Japan's Ogasawara Islands and Kamchatka in Russia's far east are also possible, albeit logistically challenging. Dominica remains high on my to-do list for 2024. For my first attempt to photograph these majestic creatures, I embarked on a long journey to the Azores in the North Atlantic. Here, under a special permit granted by the Regional Environment Directorate, visitors are allowed to enter the water with the sperm whales that gather there to mate and calf during the European summer.

The picturesque islands of the Azorean archipelago are the peaks of a remarkable chain of underwater mountains, some of the highest in the world, rising approximately 4,000 meters from the incredible Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Located far enough south to be influenced by the Gulf Stream, the islands sit atop a deep-water ecosystem that serves as a beacon for marine life. September offers optimal conditions, including excellent visibility, reasonable water temperature, fewer tourists, and the end of the calving season, providing the highest chance of encountering curious juvenile sperm whales.

Whale Spotting in the Azores

The Azores have a long tradition of shore-based whaling, which involved lookout points called vigias situated strategically around the islands to provide near-panoramic coverage. Skilled whale spotters could not only spot the “blow” of a whale up to 50 kilometers out to sea but could also identify the type of whale.

Ironically, the same methodology is still used today to spot whales and guide whale-watching boats towards them, although mobile phones have replaced the originally used elaborate white sheet signaling.

Sperm Whale Encounters in the Azores

The exact number of sperm whales in and around the Azores archipelago remains unclear. However, a reasonable estimate suggests there are approximately 2,500 individuals, resulting in roughly one sperm whale per square kilometer in an overall area of just under 2,400 km².

Sperm whales are gregarious animals that often form social groups at the surface, accounting for about 25% of their time. The remaining 75% is spent hunting in the depths for food, which can last up to an hour. Therefore, when encountering a group at the surface, the opportunity for extended interaction or intimate moments is limited at best. Usually, the whales move away or dive as we approach.

And so, while we had many encounters with sperm whales during our time in the Azores, there were few opportunities for close interaction or moments of profound connection. For that, I now set my sights on Dominica.

Don Silcock

Don is Scuba Diver’s Senior Travel Editor and is based from Bali in Indonesia. His website has extensive location guides, articles and images on some of the best diving locations in the Indo-Pacific region and ‘big animal’ experiences globally.

IndopacificImage Website.

This article was originally published in Scuba Diver ANZ #57.

Subscribe digitally and read more great stories like this from anywhere in the world in a mobile-friendly format. Link to the article.