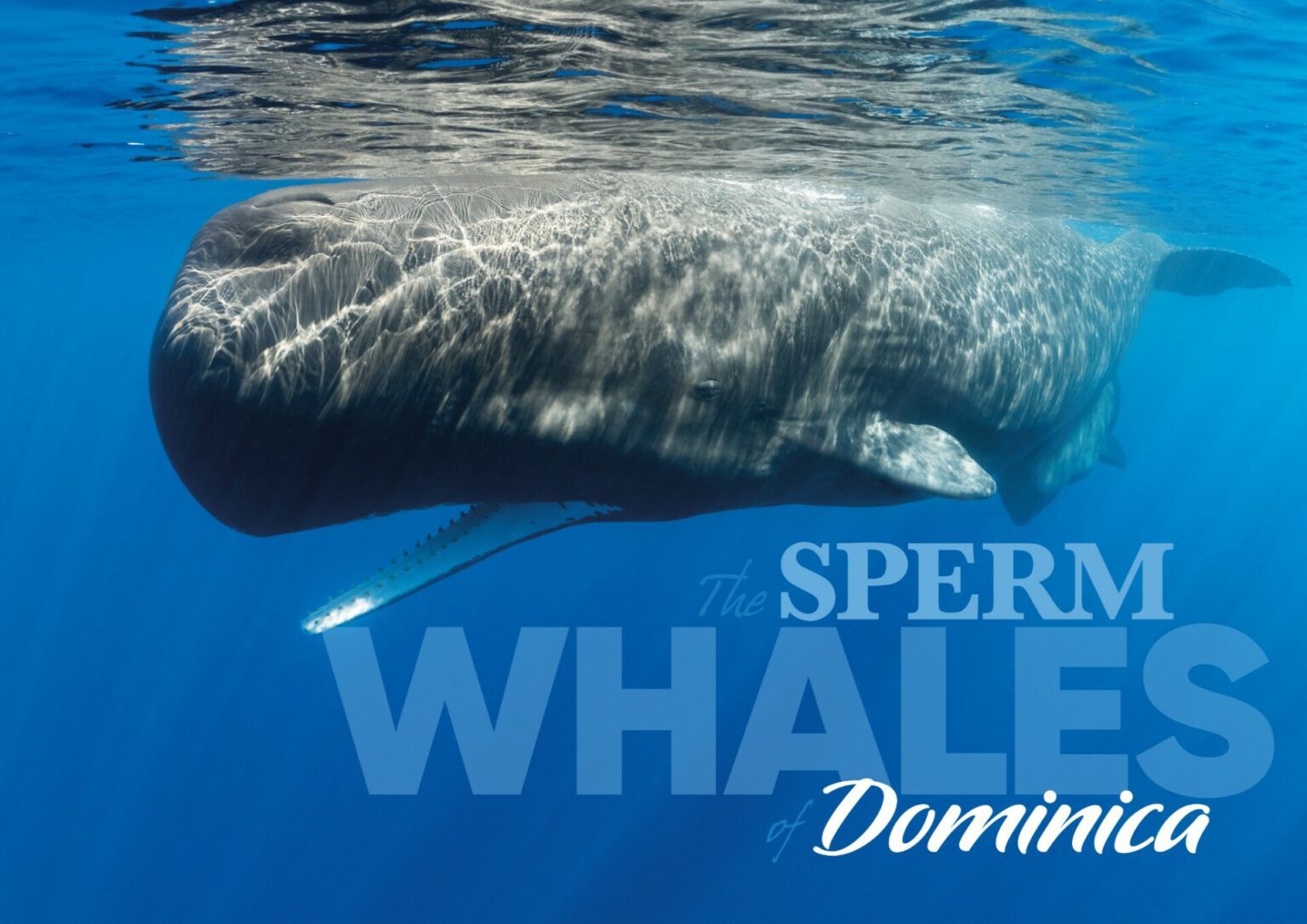

Scuba Diver North America’s Editor Walt Stearns was left awe-struck when he went diving with the biggest predator on the planet off the Caribbean island of Dominica.

Photographs by Walt Stearns

Did you know?

Sperm whales are the largest of all toothed whales and can grow to a maximum length of 20 metres plus and weight of 40,000kg, with males growing much larger than females. Sperm whales live for up to 60 years.

The poem Whales Weep Not! by D.H. Lawrence begins like this: ‘They say the sea is cold, but the sea contains the hottest blood of all, and the wildest, the most urgent’. Well, I am no whale, but my blood was certainly pumping hot through my veins in step with the wild beating of my heart as I urgently put every ounce of energy into trying to keep with a ten-metre long sperm whale.

Sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus), or cachalot as they are also called, are the largest member in the family of toothed whales. Mature males (referred to as bulls) can reach impressive lengths between 16 metres to as much as 20 metres. Adult females (referred to as cows) run significantly smaller, averaging ten metres in length. In either case, what we have is the largest living toothed predator on the planet.

In-water encounters with something this large is an undeniably awe-inspiring experience. But, if there one thing that I have learned from prior encounters with whalesharks, humpback and pilot whales is that when something this large appears to be hardly moving, it’s still likely moving faster than you! The notion of pulling any further ahead was becoming more futile by the second, with every breath through my snorkel coming in a torturous series of gasps.

Sperm whales are not the most-elegant-looking member of the whale and dolphin family. The most-obvious feature one cannot ignore is their giant bulbous head. Referred to as the melon, this portion of the whale’s body can encompass up to 40 per cent of its overall length. It is that same massive head region where the name sperm whale originated.

During the heyday of 18th century commercial whaling, whalers mistook the enormous region known as the case, which contains a white oily liquid, as the whale’s seminal fluid. Dirty jokes aside, the spermaceti organ, which possesses as much as 2,000 litres of this fluid, serves the whale as a highly specialised directional amplifier devoted to sound generation.

Did you know?

Sperm whales’ heads are filled with a mysterious substance called spermaceti.

Like all toothed whales and dolphins, sperm whales emit a wide range of high-frequency clicks for echolocation. This allows them to see using sound, while a different set of clicks and whistles are used as a means for vocalised communication.

What makes the sperm whale unique is that they can essentially pump up the volume, hammering out as much as 230 decibels (re 1 µPa m) in a single burst underwater, making them the loudest sound-producing animal on the planet.

In big animal encounters, what most of us hope for is a demeanour of mild curiosity rather than an air of partial indifference as the animal barely registers you on their radar. Well, be careful what you wish for!

After managing to take in a deep enough breath to drop down a few metres for a more-desirable camera angle, the view through my camera’s viewfinder during the whale’s oh-so-casual pass became essentially a wall of black.

And I was using a full-frame fish-eyed lens, through which objects are closer than they appear. Peeking over the top of my camera housing, I realised that the side of the whale’s head was less than an arm span away.

Then, the whale began to turn its body slightly more broadside to get into better view of me. In that moment, the encounter had turned from a hard-pressed swim to a stationary stare-down in which time seemed to come to a standstill, with the whale gazing at me.

You know the adage ‘the eyes are the window to your soul’. If Shakespeare had met a sperm whale, he might have paraphrased it differently in this case, with ‘an eye is a keyhole to the soul’.

This peculiar point of view (excuse the pun) is due to sperm whales having unusually small eyes in relation to their massive bodies. The eye was not much larger than a golf ball.

But behind that small eye is one of the largest brains in the animal kingdom – more than five times larger and heavier than our own. I marvelled at the fact that something with such a large brain is also capable of showing complete benevolence to humans.

This truck-sized creature could have easily squashed me like a grape, but instead spent a few moments puzzled by how the pathetically poor-swimming creature next to it even got here.

“ One thing that I have learned from prior encounters with whalesharks, humpback and pilot whales is that when something this large appears to be hardly moving, it’s still likely moving faster than you! ”

How big do sperm whales get?

Although there is some disagreement as to the accuracy of the New Bedford whaling fleet logs during the mid-1800s, which was the height of Yankee whaling, records of adult males taken up to 24 metres in length is very compelling.

Particularly compelling is the historical account of one such bull sperm whale that sunk the American whaling ship Essex in 1820 by ramming it.

This is the very same account that inspired Herman Melville to incorporate the attack into the storyline of his classic Moby Dick in 1851.

Did you know?

Sperm whales receive their name for the massive spermaceti organ located in the forehead region. This organ can hold up to 2,000 litres of wax-like oil. Some scientists believe that variations in oil density may assist the sperm whale in adjusting its bouyancy during dives.

The spell was broken by the sound of my camera’s shutter working in rapid-fire succession, ripping through 12 frames at a rate of three frames per second. Then, with a single beat of her tail, she surged far ahead, leaving me with nothing to do but watch her continue on her leisurely course.

Catching my breath on the surface, our whale guide Arun ‘Izzy’ Madisetti said ‘it’s the way some encounters go. Some days they play it easy, other times it’s like racing a Ferrari with a mule cart’.

Dominica, there be whales here

Dominica is located between the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, midway down the Lesser Antilles island chain. Nicknamed the Nature Island, much of Dominica’s 300 square miles of mountainous terrain remains cloaked in rainforests filled with endemic flora and fauna, rivers and waterfalls.

The island’s volcanic origins remain in the form of geothermal vents that release boiling water around parts of the island. Some, forming hot springs, are safe to soak in.

Dominica has the unique distinction of being one of only three really accessible places in the world where you can swim with these majestic, open ocean giants.

Did you know?

Sperm whales receive their name for the massive spermaceti organ located in the forehead region. This organ can hold up to 2,000 litres of wax-like oil. Some scientists believe that variations in oil density may assist the sperm whale in adjusting its bouyancy during dives.

The drill

Sperm whales are pelagic in nature and typically on the move. They have a range that spans all major oceans, but there are cases such as Dominica where they may stay put for a time.

Dominica’s own cetacean research and management programme has collectively identified and cataloged up to 30 different year-round resident pods of sperm whales, with each pod comprised of family units of four to seven individuals living co-operatively together as they protect and nurse their young.

“ Sperm whales are the second-deepest diving air breathing animal on the planet, exceeded only by the Cuvier’s beaked whale.

They can plunge as deep as 2,250m ”

Absent from these groups, except during mating season in the winter, are the larger mature males. They generally live solitary lives and will sometimes form bachelor groups as they range further afield in colder waters where larger prey resides.

Swimming with these giants typically involves long periods of tedium randomly interrupted by bursts of excitement and anticipation. First, after getting off the dock each morning, the boat crew must determine where the whales are at. This means going six to 12 miles offshore, as this is where the whales hunt squid in deep waters.

During the hunt, sperm whales will dive for 40 to 50 minutes at time, with surface intervals of ten to 20 minutes in between. Sperm whales are the second-deepest diving air breathing animal on the planet, exceeded only by Cuvier’s beaked whale. They can plunge as deep as 2,200m. While down, they may travel up to half a mile or more before surfacing, so the trick is to be there when they come up.

To determine where to be, our guides would hang a directional hydrophone overboard to listen for the clicks the whales make during their dive, using that information to identify the direction the whales are working. Once a whale surfaces, the captain then slowly coasts the boat ahead of the whale’s path, affording swimmers a chance to slide in and wait for the whales to make the next move.

Dependent on their mood, interactions with these big girls can run from as short as a few seconds to as long as an hour. These longer sessions most often to take place when a calf in the two- to four-year-old range is present.

To make sure encounters are kept as low-impact as possible, in-water whale excursions are limited to three snorkellers plus a whale guide at any one time, and require a permit, which is issued on a limited basis by Dominica’s Dept of Agriculture and Fisheries.

To ensure everyone gets a fair shot, groups are usually limited to six people. This actually works better for underwater photographers than it does for the whales, as it reduces the probability of getting in each other’s way for the shot.

As for the whales, the presence of swimmers is likely old hat, as this programme has been going on for a number of years.

This article was originally published in Scuba Diver UK #76.

Subscribe digitally and read more great stories like this from anywhere in the world in a mobile-friendly format. Linked from The Sperm Whales Dominica