Lawson Wood takes a closer look at fish without scales which attach themselves to rocks, seaweeds and other animals or fish.

Photographs by Lawson Wood

I always a remember a rather sad old joke about ‘bottomdwelling scum suckers’, but these fellows found around our local shores are very adept at life in the sublittoral zone, where they are able to attach themselves to kelp fronds and rocks to avoid the worst of the sea swell as it smashes against our rocky shores.

Common Suckerfish Species Around the Globe

For those of us who venture further afield, we are all familiar with the striped remora or sucker-fish (Echineus naucrates) which are usually seen attached to turtles, manta rays, dugong, nurse sharks and whalesharks. There are also a couple of other suckerfish in the Red Sea and more tropical waters and these include the yellow-striped clingfish (Diademichthys lineatus) and the feather-star clingfish (Discotrema lineata). In the Caribbean a very similarly shaped and coloured clingfish to our ruby suckerfish is the red clingfish (Acyrtus rubiginosus) and is usually found on soft coral fans in the twilight hours.

Suckerfish Varieties Near Our Shores

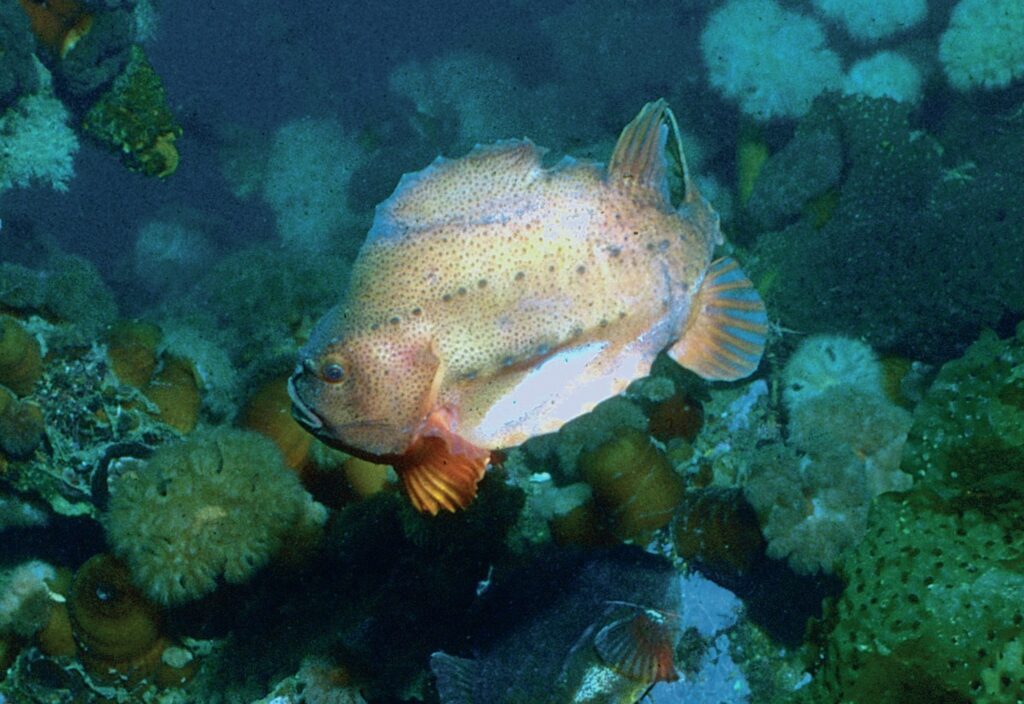

Around our shores there are quite a variety of clingfish or suckerfish and all have a specialised ventral suction disc which is adapted from their ventral fin rays. The largest of these critters is the lumpsucker (Cyclopterus lumpus). This species is as rare as it is unusual and are widely distributed from the Arctic Sea south to Portugal, and from the Hudson Bay south to Maryland, and although not widely known, rarely seen or caught, it can be quite common in localised areas.

I have photographed them and one of their cousins in Newfoundland and, of course, all around the northern coastline of the UK. They are highly prized by otters and seals and while their suction discs are large and effective, sadly, one of the first indications that they are around our coastline is when they are found dead on beaches after being thrown up by a particularly savage stormy sea.

Habits and Habitat of the Lumpsucker

This bottom-dwelling fish can be found in depths from very shallow water to beyond the 300m area. During latewinter and early spring, they swim up into shallow water, sometimes even into the intertidal zone to breed, where the water is much more oxygenated, hence the problem with winter storms, which can wipe out entire breeding areas.

The Unusual and Rare Lumpsucker

The species is fished commercially in Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea for its roe, unfortunately this has been unchecked over many years, with no thought to the conservation of a sustainable fish stock population that in some areas of the Baltic Sea, the indigenous fish stock is almost completely wiped out. Over 100,000 tonnes of lumpsuckers are also landed each year in Denmark, with the flesh often smoked as it is rather gelatinous in texture.

Once a favourite dish in European restaurants, it is no longer in demand and has little or no commercial value attached to the carcass. It is the roe which offers the greatest reward, extracted by cutting open the female, scooping out the eggs and discarding the rest of the fish. The roe is dyed, preserved and sold as lumpfish caviar – although the eggs are much larger, they are sold at around a 20th of the price of real caviar.

Physical Characteristics of the Lumpsucker

The female lumpsucker is considerably larger than the male, growing as large as 60cm. The male is only half this size. Female lumpsuckers are bluish-green or greyish-brown in colour with a paler under surface, the males are more red in colour. The suction disc is a creamy colour and is formed by a modification of the ventral fins.

The fish has no scales and has a massive, tall, rounded body, covered in bony plates arranged in four rows, which stick out as hard lumps, running backwards from the bony head to the tail fin along the side of the body. The females have a much more pronounced ‘hump’ than the smaller males, the fish also have no swim bladder and are more commonly known as the sea hen, lump hen or lump.

The dorsal fin is placed far back behind a high distinctive dorsal ridge, which is higher and more pronounced in the female than in the male. The female pectoral fins are also much smaller than the male’s. You can see quite clearly in young lumpsuckers that there are two dorsal fins, but as they grow older the first dorsal fin becomes overgrown in skin and forms part of the dorsal ridge.

Did you know?

The small-headed clingfish is known as a ‘clingfish’ because they cling to the underside of rocks on the lower shore or rock pools. They have adapted pelvic fins that form a suction cup that allows them to cling to the rocks in their habitat.

Their diet is quite varied and from captive specimens in larger aquaria are known to include small crustaceans, fish, molluscs and jellyfish. Both sexes are the same drab colour until the start of the breeding season, when the male changes to a rusty, reddish hue, starting on the belly and covering the flanks. Laying around 80,000 – 130,000 eggs in their clutch, the females disappear back out to deeper water and only immature females or late layers are seen during the rest of the breeding season.

The red coloured males stay to look after the eggs and will blow fresh water over the egg mass to help oxygenate them. Many nesting sites are used regularly and in some cases by the same fish. The eggs, when first laid, have one or two indentations in the mass to help aeration and are grey to red in colour and turn into an opaque green before hatching.

Breeding Season and Parental Devotion of the Male Lumpsucker

Few fish show such parental devotion as the male lumpsucker. Rarely leaving the nest, even to defend himself or eat, he clamps himself firmly to the rock with its head only centimetres from the nest to oxygenate the egg mass by fanning his fins or blowing water. His large bulky, angry appearance generally serves to deter predators and the guarding lumpsucker will also remove any marauding crabs or starfish. Divers can approach the lumpsucker fairly easily and may not succeed in disturbing it at all, but if so, the male will only swim a short distance and then return once more to its duty.

Over a period of four to eight weeks, the eggs finally hatch and the 6-7mm tadpole-shaped young emerge to spend summer in the kelp. Larvae and juveniles are planktonic, often attaching themselves to floating bits of detritus and weed.

The young are very difficult to spot in the kelp as they change colour to suit their background and have a dull scale-less skin usually greenish brown in colour; they have a pair of almost iridescent strips which run from the lip to behind the eyes.

They already have a suction disc formed when they are born. This they use effectively to attach themselves to the underside of kelp fronds where, when danger approaches, they curl their tail around their head and lie very still, resembling blobs of jelly or small tunicates. Lumpsuckers are slow growing and only reach 5cm in the first year, reach sexual maturity when they are three years old, and fully mature specimens at five years old.

Threats to Lumpsuckers

Lumpsuckers are clearly widely ranged and in some areas of the Baltic in particular are prolific, as it would appear that their main predator is us in the collection of their roe. Lumpsuckers also fall prey to halibut, dogfish, sharks, whales, dolphins, anglerfish, otters and seals. Seabirds often attack them during spring tides when they are in much shallower water, but it is the heavy swell sea conditions most prevalent in the spring that take the largest toll, other than for commercial harvest.

Lumpsuckers move quite fast in short bursts of speed and eat small gobies, blennies, crustaceans and comb jellies, although they do not feed at all during the breeding season and whenever you are photographing them, they must be approached sympathetically and carefully. There is another true species of lumpsucker (Eumicrotremus spinosus) which is often caught in the Arctic region of the western Atlantic, usually in depths of less than 25m. Very similar to Cyclopterus lumpus, it has much larger conical tubercles along the margins of the body. The examples here were photographed off Bell Island in Newfoundland.

Other Species with True Suction Discs in British Waters

In British waters, the similar species which have true suction discs include the much smaller sea snail or unctious sucker (Liparis liparis) and Montagu’s sea snail (Liparis montagui). Similar species are the shore clingfish or Cornish sucker (Lepadogaster purpurea) and the Connemara clingfish (Lepadogaster candollei) which also have ventral suckers and are widely distributed on both sides of the Atlantic from Scandanavia to Madeira, Senegal and the western Mediterranean.

Both Liparis species are fairly common in shape (almost tadpole like) with the sea-snail or unctious sucker having a rounded front and its dorsal and anal fins appear to join onto the tail. It too has a sucker disc formed from the modified pelvic fins and is usually some drab colour like kelp to match its environment. It will also have a series of indistinct streaks and lines. It can grow to 12cm but is usually much smaller than this and feeds on small crustaceans.

The Montagu’s sea-snail (Liparis montagui) is also a small tadpole-shaped fish with a large and broad, rounded head, tapering to a thin tail. Similar to (L. liparis), it has a single long dorsal fin, however in this case, the fin is not joined to its tail and is usually reddish-brown in colour. Hiding among kelp, its bright colours make it fairly easy to spot. It can grow as large as 10cm. Its pelvic fins have formed a strong suction disc and it enjoys depths from the rocky shore to 30m.

The Cornish sucker or shore clingfish (Lepadogaster purpurea) has a body which is flattened sideways and with a head that slopes gently into a long, duck-billed snout. Its dorsal and anal fins are attached to the tail and it will have bluish spots or blotched markings behind its head. This fish is also identified by its pair of fleshy ‘tentacles’ just in front of the eye. Variable in colour, they are found throughout the range of the North Sea and western Atlantic and grow to around 7.5cm. This species is almost identical to (L. lepadogaster) however this species is more commonly found off the west coast of Galicia in Spain, Portugal, Canary Islands and south to Morocco and Senegal.

Closely related is the Connemara clingfish (Lepadogaster candollei) but noticeable by not having ‘tentacles’, rather just a flap of skin and the dorsal and anal fins are separate. Variable in colour but usually in shades of reddish brown, they have an obvious ‘duck-billed’ shape to the head and often has a prominent white line stretching over the head between the prominent eyes.

The Uniqueness of Ruby Suckerfish

More difficult to identify is what I believe to be the ruby suckerfish (Apletodon dentatus), which can grow to around 5cm. This clingfish has a body flattened sideways and a head flattened from above and has its suction disc under the front part of the body. It has enlarged cheeks and fairly large eyes and a wide mouth. It feeds on small crustaceans and starfish and enjoys all habitats. It will change colour to suit its environs, but is more commonly reddish-brown and covered in small spots.

Conclusion: The Fascinating World of Suckerfish

These small fish are another species often overlooked in the hunt for critters to photograph, but if you spend some time amongst the kelp along the shoreline, you will be rewarded by these amazingly specialized fish from the large ‘football’ shaped lumpsucker, all the way to the much smaller ruby suckerfish.

This article was originally published in Scuba Diver UK #74

Subscribe digitally and read more great stories like this from anywhere in the world in a mobile-friendly format. Link to the article.