Why is a German Navy underwater? Why and when did it happen? What’s the attraction, and why are we still diving these wrecks more than 105 years later? Lawson Wood explains the lure of Scapa Flow.

Just a short ferry ride off the north coast of Scotland lie the Orkney Islands. Created by submergence, the islands of Orkney give the impression of tipping westwards into the sea and there are great sea stacks, arches, caves and caverns all around the coast, some of which are world famous, such as the Old Man of Hoy.

On the same latitude as southern Greenland, Alaska and Leningrad (all places which are synonymous with extreme cold), Orkney is bathed in the warm waters of the North Atlantic Drift that first started out as the Gulf Stream in the Caribbean. Subsequently, the islands have a fairly equable climate and sea conditions are generally fair all year round.

To its credit, Orkney has the almost-perfect naval base with calm sheltered waters surrounded by protective islands, creating a deep natural harbour first named by the Vikings. Scapa Flow to the south of the islands was the base chosen by the British Naval Fleet having been used over several generations and had already served the nation well during the Napoleonic War and the American War of Independence.

The large natural harbour of Scapa Flow has a protection of surrounding islands and was therefore the perfect place for housing the combined navies from two countries.

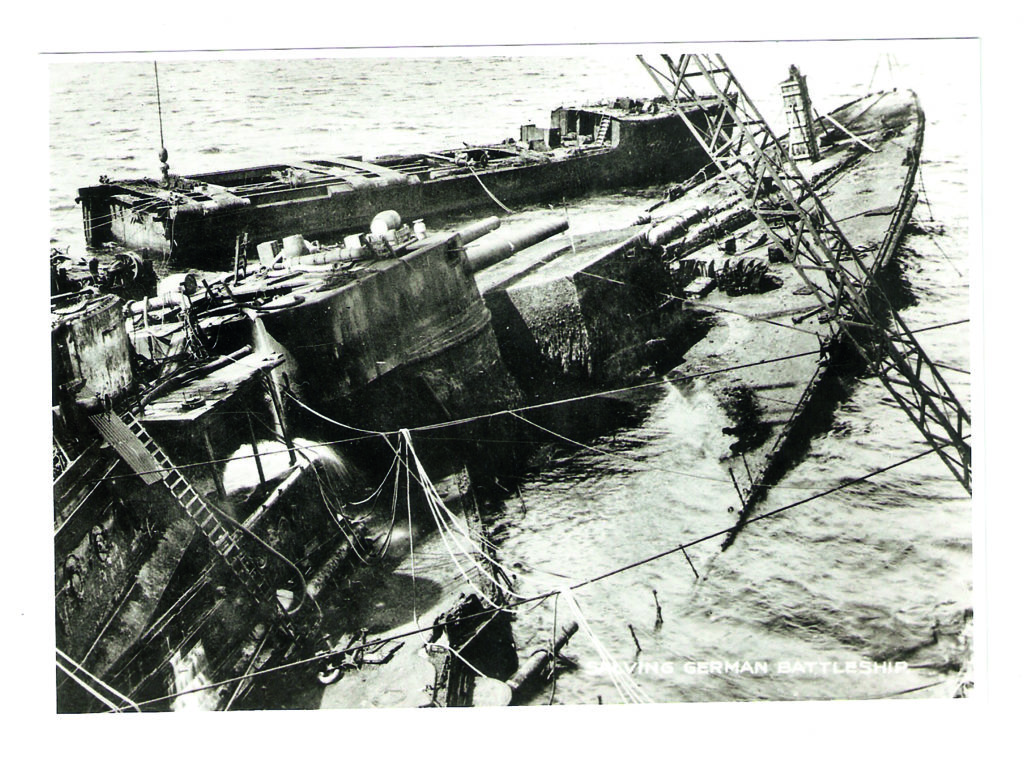

As a direct result of the negotiations of surrender within the armistice terms at the end of World War One, it was agreed that the entire German High Seas Battle Fleet would be interred in Scapa Flow, the base of the British Home Fleet. On 23 November 1918, the people of the Orkney Islands woke up on a cold winter’s morning to the most-amazing spectacle of the largest assembly of naval shipping on the planet. 96 ships and over 70,000 men all appeared out of the early morning mist.

This included 74 German naval ships and comprised of her top 11 battleships and five battlecruisers.

Due to the ignominy of this surrender and internment, the German fleet’s commander, Ludwig von Reuter, took it upon himself to scuttle the entire fleet lest it fall into the hands of the Allies.

Taking advantage of the coincidence of the almost-entire British Fleet leaving on exercise at the same time, with the aid of various coded messages within the fleet, von Reuter co-ordinated the sinking of the entire German Fleet on Midsummer’s Day, 21 June 1919.

This was the largest intentional sinking of any ships, anywhere in the world, at any time, before or since. Over 400,000 tons of enemy shipping sunk that day.

Several salvage companies were employed in raising the fleet and between 1923 until the mid-70s, these ‘scrappers’ systematically raised, scrapped and reduced these sunken ships into their constituent parts (some of which were then resold back to Germany to help build their next fleet as events moved steadily towards a second world conflict!).

When war broke out once more, the British Admiralty did not expect a hostile intrusion into the base of the Home Fleet, however, just six weeks after the outbreak of war, the German U-Boat U47 gained entry into the Flow and sank HMS Royal Oak with the loss of 733 officers and men.

Until this time, the open sea entrances into Scapa Bay were protected from enemy shipping by various booms, nets, barriers of various varieties and principally by placing derelict ships, which were sunk as ‘blocking’ or block ships.

As a direct result of this overwhelming and tragic attack, Winston Churchill visited Orkney and ordered the building of the Churchill Barriers. Built by over 1,400 Italian prisoners of war, the Italians not only left behind a lasting legacy (of hardworking, expertise, friendship and respect), they also built a chapel out of a disused Nissan hut. The ‘Italian Chapel’ is fully restored by the original artist and is a must see when visiting the islands.

Scapa Flow has now risen to become one of the top scuba-diving destinations on the planet with wrecks dating from the world’s last great conflicts. The German fleet wrecks are located in the centre of Scapa Flow near an obvious outcrop of rocks, the Barrel of Butter.

The Blockships to the west in Burra Sound are visited by the day diveboats, but only at slack water. The Blockships to the east at the Churchill Barriers are done as shore dives.

Scapa Flow is undoubtedly recognised as the best wreck diving in Europe and certainly ranks in the top five of the world. There is more wreckage in Scapa Flow than any other location on the planet. At present there are still three German battleships; three light cruisers; one mine-layer; five torpedo boats (small destroyers); a World War Two destroyer; one submarine; 27 large sections of remains and salvor’s equipment; 32 Blockships and two British battleships (the Vanguard and the Royal Oak – restricted War Graves); a further 19 identified British wrecks and many other bits of destroyed aircraft; supply barges and shipping wreckage as yet, still unidentified.

Diving The Flow

Sitting in the early morning calm, the cold air of daybreak was leaving a slight foggy residue around the dive boat. We could see no land, or in fact any other living thing, except a tiny orange marker buoy with a frayed bit of line attached. I could hear seagulls, but couldn’t see them, indicating that we were fairly close to some land mass, but it was invisible.

The natural harbour of Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands has the largest concentration of shipwrecks in the world and I was about to dive on one of those ancient warhorses, in both eerie and spectacular fashion.

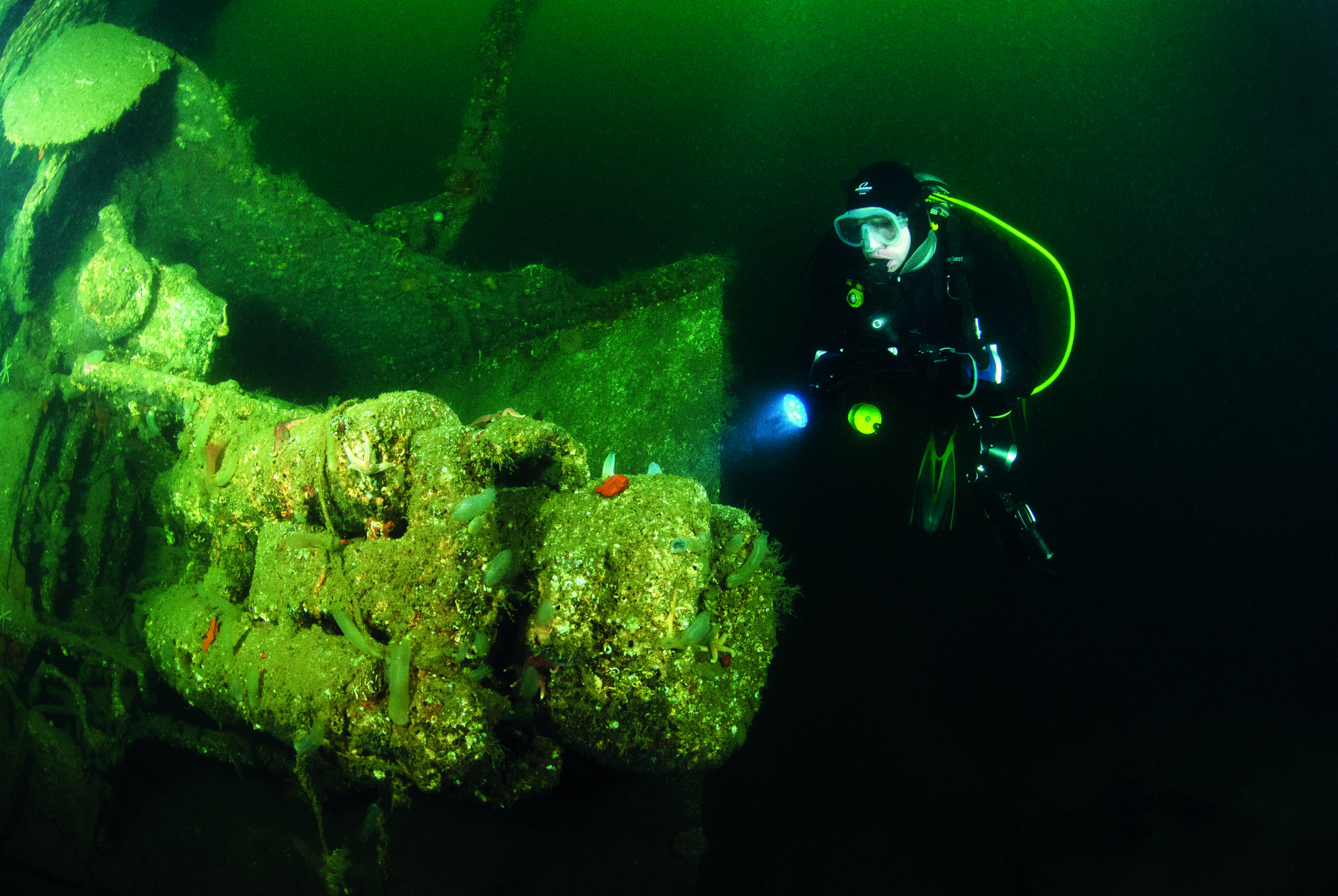

This dive is set in a bay amid some of the most-dramatic scenery in Europe, considerably heightening the diving experience. Jumping into the water, the first cold splash of water on my face almost took my breath away. Soon though, my training took over and I dropped down the shotline from the buoy, dropping through 25m of water to arrive near the stern of a German light cruiser called the Karlsruhe, just one of the three remaining German light cruisers, one mine-layer and three battleships which were scuttled in 1919.

Through the descending gloom, the graceful arch of the stern approached and my dive buddy and I dropped to the shelly, stony seabed to gaze upwards in awe at this massive ship lying on her starboard side. The hull is completely festooned in plumose anemones (Metridium senile) and feather starfish (Antedon bifida).

From here we swam along the remains of the near-vertical decking, past the superbly scenic rear guns and approached the superstructure which is mostly collapsed. Maximum depth is 27m, but with average depths much shallower than this, you do get plenty of time to make a first exploration of this amazing shipwreck, but all too soon it is time to make the way up the mooring buoy line to the dive boat. The Karlsruhe is regarded as one of the wrecks often seen as a ‘training’ dive before facing the rest of the deeper German fleet, but in reality it is a superb dive and most divers plan to explore the wreck more than once during a week’s dive trip.

Over the years, a certain unfounded and unjust notoriety has evolved when talking about diving on the wrecks of Scapa Flow. Nowadays, divers are more informed, better trained and have the very latest of diving computers to guide them through the complicated variables of multi-level diving. For those divers who only use air or nitrox, all of the wrecks can be dived without any decompression penalties.

Yes, this may cut down your time on the wrecks, but no matter what your level of expertise is, safety should always be your top priority. Those doing more technical diving with trimix and closed circuit all have their own sets of rules with extended time on the wrecks, but inevitably the penalty of this diving time at depth results in the length of time taken to get back up to the surface safely.

This can also dramatically reduce your range of dives in a week’s diving in Scapa Flow. In reality, diving in Scapa Flow should never be overlooked or even passed over by anyone – no matter what the level of expertise is.

The diving is actually fairly simple and uncomplicated – jump off a boat, dive down a shotline, do some wreck exploration and perhaps some photography within your time limit, back up the shotline and onto the boat again!

The shallowest parts of the German Fleet are in only 15m and the shallowest blockship remains are in less than 6m, so the wrecks of Scapa Flow are well within the reach of every diver.

All of the shipwrecks in Scapa Flow have protected status under the Protection of Wrecks Act 1974 and are scheduled under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas 1979. For those visitors who do not understand what this means – do not penetrate the wrecks; do not touch and do not remove any ‘souvenirs’! For those who do, you will be arrested, taken to court, heavily fined and may have the possibility of incarceration.

The natural harbour of Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands has the largest concentration of shipwrecks in the world

The diving is actually fairly simple and uncomplicated – jump off a boat, dive down a shotline, do some wreck exploration and perhaps some photography within your time limit, back up the shotline and onto the boat again!

Lawson Wood: Biography -Lawson Wood is from Eyemouth in the southeast of Scotland and has been scuba diving since 1965. Now with over 15,000 dives logged in all of the world’s oceans, he is the author and co-author of over 50 books, including some specifically on Scapa Flow and the Orkneys. He made photographic history by becoming a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society and the British Institute of Professional Photographers solely for underwater photography. He is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. Lawson is founder of the first marine reserve in Scotland, co-founder of the Berwickshire Marine Nature Reserve and co-founder of the Marine Conservation Society.

Photographs by Lawson Wood