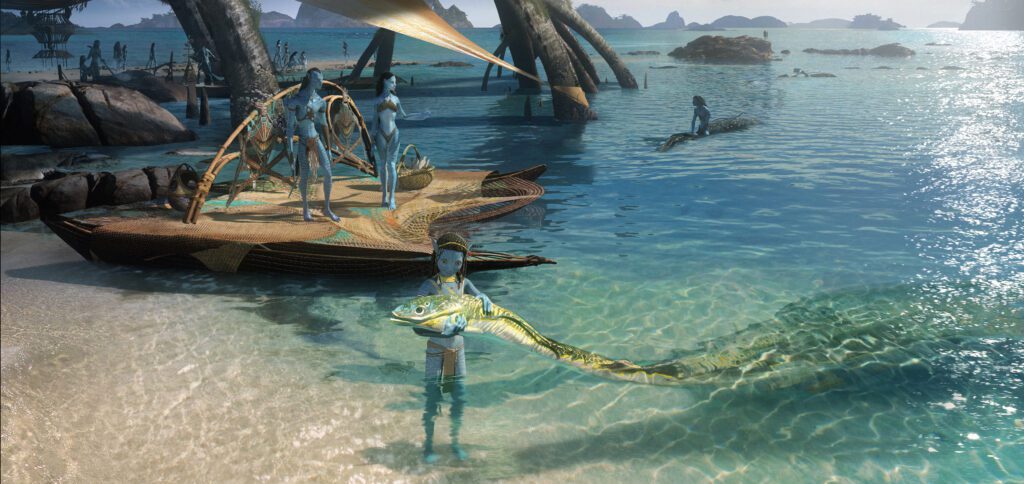

Avatar: The Way of Water looks set to be one of the most mind-blowing movies ever made, and it obviously has a huge underwater element to it. We spoke to two of the pros – John Garvin and Kirk Krack – who provided the expertise to bring these scenes to life.

Q&A: John Garvin

We chat to technical diving instructor and screenwriter John Garvin about how he got started in diving, his cave-diving exploits in the Caribbean, and his work behind the scenes on Avatar: The Way of Water.

Q: As we always do to kick off these interviews, how did you first get into diving?

A: While I am now settled in Australia, I am originally from Blackpool in the north of England. I got into diving through the BSAC route, starting at university, and actually, coming full circle, it is all James Cameron’s fault – I was inspired to go diving after watching The Abyss, and blew my whole grant cheque on buying a full set of second-hand gear. I subsequently became a BSAC Advanced Instructor with a club in Manchester and spent many weekends travelling to some of the most-popular dive sites around the UK, as well as any quarries or inland sites we could just get wet in.

Q: You were an early adopter of closed-circuit rebreathers and that technology has been close to your heart ever since. What is it about CCRs that capture your imagination so much?

A: After going the recreational instructor route, I initially got into teaching technical diving with DV Diving in Bangor, Northern Ireland. I finally saw the light after ten years of diving in the UK and moved to the Turks and Caicos Islands to open a technical-diving school, where the warmer water, clearer visibility and wall systems provided much more conducive conditions for teaching advanced-level diving and closed-circuit rebreathers. I was one of the chaps who managed to get in on the bottom floor of CCRs, and in particular the AP Diving Inspiration – I was one of the first instructors teaching diving on this unit in the region. I had an awful lot of Americans coming over to learn to dive CCRs, and this is where I kind of segued into film work – some of the people who were coming over for CCR training wanted it as a tool to spend longer underwater and film. Some were involved in documentaries like Blue Planet, and they wanted the benefits of four-hour dive times, no bubbles and getting closer to sealife.

Q: You spent many years in the Turks and Caicos Islands, not only diving and teaching tech diving in the tropical waters surrounding the islands, but also exploring the many caves. What was it about venturing into the unknown underground that inspired you?

A: I was teaching full-time over there, and really needed kind of an escape for myself – I think if you don’t do your own type of diving, if you are only teaching all of the time, you can get burnt out pretty quickly. Someone handed me Rob Palmer’s book Deeper into the Blue Holes, and Rob had been exploring all of the Andros systems further up the chain in the Bahamas, and everything he described in this book was basically there in the T&Cs, except that none of the systems there had been explored. I had no experience in caves, but I was a tech-diving instructor, and just applied all of the things from wreck diving to give it a go with a friend of mine. We nearly came a cropper on that very first dive in Cottage Pond, but luckily we surfaced. That was it, I was hooked – but I went to Florida to get properly trained with Tom Mount – and then spent ten years mapping cave systems on the islands.

Q: Talking of CCRs, it was training the actors on Sanctum – for which you wrote the screenplay – to dive and then use CCRs that first introduced you to James Cameron, and you have since gone on various adventures and expeditions together. Before we get on to Avatar: The Way of Water, what are some of your most stand-out experiences with Cameron?

A: I have worked with James Cameron on numerous projects, the biggest ones being Sanctum, that was my first one, and then a little later on, Deep Sea Challenge, which was the submersible we built in Sydney, and I was responsible for the pilot sphere, so everything that went inside the sub and pilot safety. We used and developed CCR technology for his life-support system inside the sub. I then went on to work on Avatar and some other projects with him.

I think that period in Sanctum, where we had to train the actors, first of all how to dive, and then train them how to cave dive, and then just as they were reeling from that, how to cave dive using CCRs and full-face masks. It was a massively task-loading process, but the cast did all their own underwater scenes – it really is them on screen – and I think this helped build Jim’s confidence in my abilities, along with keeping him safe on Deep Sea Challenge with the rest of the team, and this got me the gig on Avatar.

Q: So, Avatar: The Way of Water. This has to be one of the most-anticipated sequels ever, and one of the main reasons for this has to be the underwater sequences. What was it like to get asked to be involved in this mammoth project in the first place?

A: James Cameron knew that we would have some of the same issues we’d had on previous projects – complicated technology underwater, thousands of hours underwater with relatively new divers, we had to keep it safe, first and foremost, so I was brought on board relatively early on, and I was partly responsible for putting together a team of 25 divers in total, all from different departments, that allowed us to safely shoot Avatar underwater.

Q: What elements of the in-water work were you involved in the most?

A: Avatar: The Way of Water was a wonderful cross-match between technical diving and freediving, and technical freediving, using nitrox mixes and all the rest of it, which was key to our success, but one of the more rewarding aspects of my job was to help consult and design, test and build, lots of the really cool toys used by the ‘humans’ – the underwater dive-equipment systems, the full-face masks, and so on.

Q: What were some of the most-challenging aspects of filming Avatar: The Way of Water?

A: We had to crack the code for underwater motion-capture, it had never been done before. Many films chose to shoot ‘dry-for-wet’, where typically actors are in a dry studio, in harnesses in front of a green screen, and special effects are added later to make the hair move and show bubbles. But as any diver will tell you who has dived in a strong current, or used a DPV, your movements are dictated by the water, and it creates ripples on your skin, contortions on your face – I don’t care what people say, if you do ‘dry-for-wet’, it just looks fake. Divers will spot it instantly, but even non-divers will watch ‘dry-for-wet’ performance capture and sense something is not quite right, and sometimes that is enough to sever the emotional connection you are supposed to be having with that character and the story at that time. Of course, Jim Cameron being a diver, he wasn’t going to have that, and so all of the underwater scenes were shot for real underwater.

Before we did that, we had to crack the code for motion capture. So we developed camera systems, and put the actors in wetsuits with the standard sensors, or reflectors, on them. We got to the point through specially designed cameras and by calibrating them correctly, we were getting some really good motion capture down at depth, but the problems arose when we were in the shallows close to the surface. It acted as a mirror and the sensors got confused, they didn’t know if they should be tracking, you know, the ball on Sigourney’s shoulder or the reflection. Jim describes it very well, that as soon as the actor came close to the surface, it was like when a fighter jet disperses chaff to confuse a missile system, the cameras didn’t know what to lock on to, the actor or the reflection. So we ended up using hundreds of thousands of floating balls to create a moving surface, which helped the motion capture take place, but allow the divers to surface through.

This was another reason for freediving. Divers on scuba exhale bubbles, and those bubbles similarly confused the motion capture system. Initially, I thought the only way to avoid this was to use CCRs, and so I turned up fully expecting to have to train certain members of the crew how to use them, but it ended up that Kirk (Krack) did such a great job training all of the cast and crew in technical freediving that the CCRs were not needed – they all had a working breath-hold of two and a half to three and a half minutes.

This was the initial brief that Jim Cameron gave Kirk and I. He was very clear, he wanted all of the actors to have a working breath-hold of a minute and a half to two minutes. The last thing that he wanted was the actor being out of breath at a crucial moment when trying to get the shot. He also wanted the actors to look relaxed underwater, and the only way you are going to get relaxed performances is if the actors are properly trained.

Q: As we always do to end these Q&As, what is your most memorable moment diving?

A: Ooh. I think, if I had the choice to do one more dive in my life, and go back and relive one dive. I think, I was lucky enough to be on one of the first expeditions to the Galapagos using fully closed-circuit rebreathers. I remember dropping down on the remote location of Darwin and Wolf, and just being surrounded by nature on steroids. Whalesharks, hundreds of schooling hammerheads, turtles, fish, everything – it had a very long-lasting impression, it was the most incredible display of bio-diversity I have ever seen or witnessed.

Q: On the flipside, what is your worst experience diving?

A: I was in one of these cave systems in the T&Cs. It was a very fast-flowing cave, and I was on a CCR, and this ultimately is what saved my life. We misjudged the current and a large portion of the ceiling collapsed on me at a depth of just over 60m. I was on my own, it was a tight system, and I was buried. I lost the line. I was trying to scrabble about to dig myself out, eventually found my line, and was in zero vis – I luckily took the right route out, but my buddies were very concerned, as I was 20 minutes overdue, they thought they’d lost me. I had lots of decompression to do, and a lot of serious thinking to do. It was just one of those things, it wasn’t even real complacency, it was just a wake up call about how badly things can go quite quickly on a dive. Thankfully, I know it is a cliché, but the training kicked in, and I couldn’t have been on a better piece of equipment to give me the time I needed down there. If I’d been on open-circuit, it could have been a very different outcome.

Q: What does the future hold for John Garvin?

A: There is another film project I am working on that I can’t talk about at the moment, that should be out in the next couple of years, and it has a heavy diving element. I am very much looking forward to returning to Pandora and becoming a part of the additional sequels.

I am very much looking forward to the next month. It was four years of my life spent on Avatar: The Way of Water, and I can’t wait to see the response. There have always been these key films that have come out and inspired hundreds of thousands of divers to embrace the oceans, such as Cousteau’s The Silent World, the Seahunt TV series, The Deep, the aforementioned The Abyss, – these are all critical milestones, and I really hope that when Avatar: The Way of Water is released, it is a call-to-arms for a whole new younger generation of divers to get actively involved in the sport and see the oceans in another way. I think the industry needs that as it recovers from the effects of COVID.

Q&A: Kirk Krack

We chat to technical diving instructor and freediving guru Kirk Krack about his first experiences of diving, how he became the go-to person in the world of freediving, and his work with cast and crew on Avatar: The Way of Water.

Q: As we always do to kick off these interviews, how did you first get into diving?

A: I got a birthday present of an open water course when I was 14 years old, from my parents. I’d always been a water-baby, and this was the natural progression. Professionally I got into it after doing light commercial diving in the world’s biggest water park – and then discovered I could become an instructor and go live in the Caribbean – sold! I bought my first dive shop when I was 20, sold that and bought my first resort dive centre when I was 25, which was Dive-Tech in Grand Cayman. At 32, I started Performance Freediving International, and here I am today.

Q: You became a recreational scuba diving instructor, but pretty soon progressed on to teaching technical diving, even going so far as becoming an instructor trainer in the discipline. What was it about technical diving that captured your attention?

A: I had gone as far as I could as a recreational instructor. Nitrox was just coming on to the scene, I could see some of its applications in what we were already doing, and so technical diving became the next thing to learn. It wasn’t so much to see what was down there, it was more the procedures and the technical components of executing a high-risk dive in a high-risk diving environment, what were the mindsets and the physiology I needed to learn. It just really intrigued me, and I could see there was this major opportunity in technical diving in the future. At the height of my tech diving, I was doing 170m dives, six hours plus of decompression, on a regular basis – at this time, there were only a handful of us going to these depths.

Q: Now technical diving seems about as far removed from freediving as possible, but you soon fell under the spell of diving on breath-hold. How did this love affair with freediving come about?

A: Before I got scuba lessons, I was ‘freediving’. I was a water rat. I was always in the water, I was snorkelling and skin-diving, but looking back, I realised I had been essentially freediving, going to depths, changing my breathing on the surface, and incurring all the risks associated with that, but didn’t know any better. There was no real education or training out there for freediving at this time. It was during my time on Grand Cayman that I could really see there was a future in freediving, that it was this full-on sport. My specialty was educational systems and teaching, and I designed one of the first proper ones, with standards and procedures, and brought out a whole system of education, and eventually reformed as PFI in January of 2000.

Q: You were one of the first people on the planet to develop technical freediving. This seems a bit of an oxymoron, but tell us more about what it entails.

A: The history is in Cayman, supporting Tanya Streeter on one of her world-record attempts, breathing on some left-over 80 percent on the boat while debriefing with her – I was the safety freediver/coach for her – I got back in on breath-hold to check on some divers doing deco and realised I stayed down for, like, five minutes, unaware I had gone that long as I had no urge to breathe. And then it was like, of course, the oxygen. I started playing with it over the years, and began using 32 percent on some filming projects, and you notice it. I then started using it for all of our safety freedivers, at the De Ja Blue competition. They all said – no exhaustion at the end of the day, no exhaustion after three weeks, a quicker turnaround on the surface, and just a more-comfortable breath-hold. So I was like, this is a no-brainer, so I started writing procedures and systems to be able to teach this. It took some time, but we got there in the end.

Q: Now moving on to the more-glitzy side of things – your work with Hollywood. You have trained the likes of Tom Cruise and Margot Robbie. What is it like working with superstars of that level, and do they make good students?

A: Ha, that’s a really good question. There hasn’t been one I haven’t enjoyed working with, there hasn’t been one person that wasn’t dedicated to the craft of learning what they wanted to learn. There have been a couple who did it to get the job done, but they were completely professional about it, others wanted to learn more than we needed to teach them. With Tom Cruise we went into advanced-level academics and things like that.

Q: We have to talk about your work behind the scenes on Avatar: The Way of Water, but before we get into that, is it true that your first encounter with James Cameron was when you were sat next to him on an airplane, and that ever the chancer, you gave him your business card?

A: Ha, close. I’d gone through US customs, I was in Vancouver and was getting a Starbucks, and I saw James Cameron walk by with his entourage. I just had to go meet him, I had to do the fan-boy thing, and so after I got my coffee, I went looking but couldn’t find him. Then when I got on my plane to LA, there he was, with his wife Suzy, in 1A and 1B. So I go back to my seat, pull out a business card, and on the back I write like my Twitter resume, just whatever I could fit it – and then it takes me half the flight to get up the courage. Halfway through the flight, I walked up and said ‘nothing ventured nothing gained, my name’s Kirk and I am a freediver’, and he was like ‘how long can you hold your breath?’. I thought he might have just thought ‘heh, neat guy’ and then left the card in the seat pocket in front of him, but then in 2017, I ended up going out for a meeting at his house in Malibu and he told me Avatar number two was going to be 60 percent water, and I knew this was going to be the epic of the ages for diving. He asked me what I would when it came to filming, etc, and after two hours was done, he was like ‘you’re our guy, we’ll be in touch – are you interested?’. Initially, I thought it was going to be a few months, me and some of my instructors, but it ended up being years of my life.

Q: So on to Avatar: The Way of Water. This has a massive amount of screen time that is spent underwater, and so the cast and crew had to be safe and comfortable spending hours and hours in the water. What was your main role on the shoot, and what were some of the main challenges you faced?

A: I had to teach the cast, who varied in age from six to 69 years old, and various physical abilities. I had to teach the camera people, who were all water-people, but I had to get them in synchronisation with what I was doing with the cast, and how we were going to work the cast. I had to train grips. I had to train stunt people. We did 250,000 plus freedives in two and a half years just in LA alone. We went through almost 1,500 80 cubic foot cylinders of 50 and 80 percent nitrox, not including air cylinders, in LA alone. Underwater, at one time, we had 26 people on breath-hold. We had breath-holds in the four and a half minute range, and not just static apnea, these were working breath-holds, dynamic movements. Underwater parkour.

Q: It must be quite a daunting prospect having to teach a veritable army of cast and crew to freedive to the standard Cameron needed to be able to capture the underwater sequences he wanted.

A: I had to train the cast member, and then I had to train the character. They are two separate people embodied in the same person. Sigourney Weaver was really into it, to bring her character to life, and any time she could get extra water time, when she wasn’t on set but was in town, she would – and usually it was over my lunch hour. But we’d go in and get extra training, which wasn’t scheduled. She was a lot of fun to work with.

Kate Winslet was amazing as well. She couldn’t come to LA, so I came to the UK to train her. When she heard where I was going to stay, she was like ‘no, we not having any of that’, and I ended up staying with the family. I’d have breakfast with them, then do a little academics, and then get in the pool. She just loved it. She was already a scuba diver, I think, and so she caught on really quick. She didn’t get competitive, to get this amazing time, she just really got into it. There was just this natural ability, and also the professionalism – if I am going to do this, I am going to do this well and I am going to know everything.

It was one thing I tried to instil in them, that this was going to be a long shoot, and they only knew a little bit about their character, but you didn’t know any specific scenes, and so to let James Cameron have all the tools at his disposal so Pandora could come to life, I have to equip you with a whole bunch of tools, and experiences, such that when he asks ‘Kate, I need you to do this, or that’, it was easy for me to say ‘it was when we were training like this’, and then should could pull that out of her tool kit, she’d already done, it, she knew all the procedures.

Q: As we always do to end these Q&As, what is your most memorable moment diving?

A: It’s tough because there are some many different things. When we were shooting The Cove, we were in the Bahamas and my wife Mandy and I were being towed behind a boat looking for dolphins. We couldn’t find any, but then boom, these three dolphins appeared from nowhere. The three were all playing with us, but this one particular animal really was curious – Mandy put out one of her arms and flattened her hand, and the dolphin turned upside down and actively rubbed its belly on her palm. We let go from the sleds and, for the next 45 minutes, it was so interactive and communicative. We were having this discussion on an emotional level, sentient being to sentient being, in a language we both know, it just wasn’t English. We were both crying when we surfaced, and even that night we kept thinking about it, because it touched our hearts.

Q: On the flipside, what is your worst experience diving?

A: Besides pooping in my drysuit and lifting an airplane? Well, something that has hit me recently. I founded the Exploration Diving Society of British Columbia a year or so ago, and we work in all three modes – freediving, technical and non-technical diving. Now, after many years totally focused on freediving, I am getting back into scuba, and doing trimix dives to 60m. I was so adept at technical diving back in the day, but now suddenly, there is this level of anxiety – ‘why am I struggling with this, I hate this’. I am down there, chugging like a machine, having this feeling of claustrophobia. People know me as a freediver, but I am more of a multi-discipline diver. I know I will get there again, it’s just not fun at the moment. It is more the frustration of ‘I used to be really good at this’…

Q: What does the future hold for Kirk Krack?

A: I am totally dedicated to Avatar and whatever the future sequels hold in terms of a water element. Avatar: The Way of Water is set in our reality, this isn’t the Marvel Universe. This isn’t an alternative reality, this is our reality, just 150 some years into the future. It’s James Cameron’s vision of what space travel will look like, what Pandora looks like, but here’s the cool thing, what human diving will look like – I think the scuba divers and technical divers out there will be salivating because of this vision from the world’s greatest artistic movie director. Avatar: The Way of Water will mark the next renaissance of diving, and I hope I can help the dive industry mentor this and caretake it for the long term – this is going to be the epic water movie of the generation.

I have a number of other things happening – Aquatic Safety International, which are the institutional breath-hold survival programmes, focusing on Waterborne, which will hopefully be the Instagram/Facebook gateway drug into freediving and all things water, and PFI, helping International Training continue to grow it, plus a few consulting roles.

Photographs courtesy of John Garvin, Kirk Krack and 20th Century Studios. © 2022 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.