How did you get started in underwater photography?

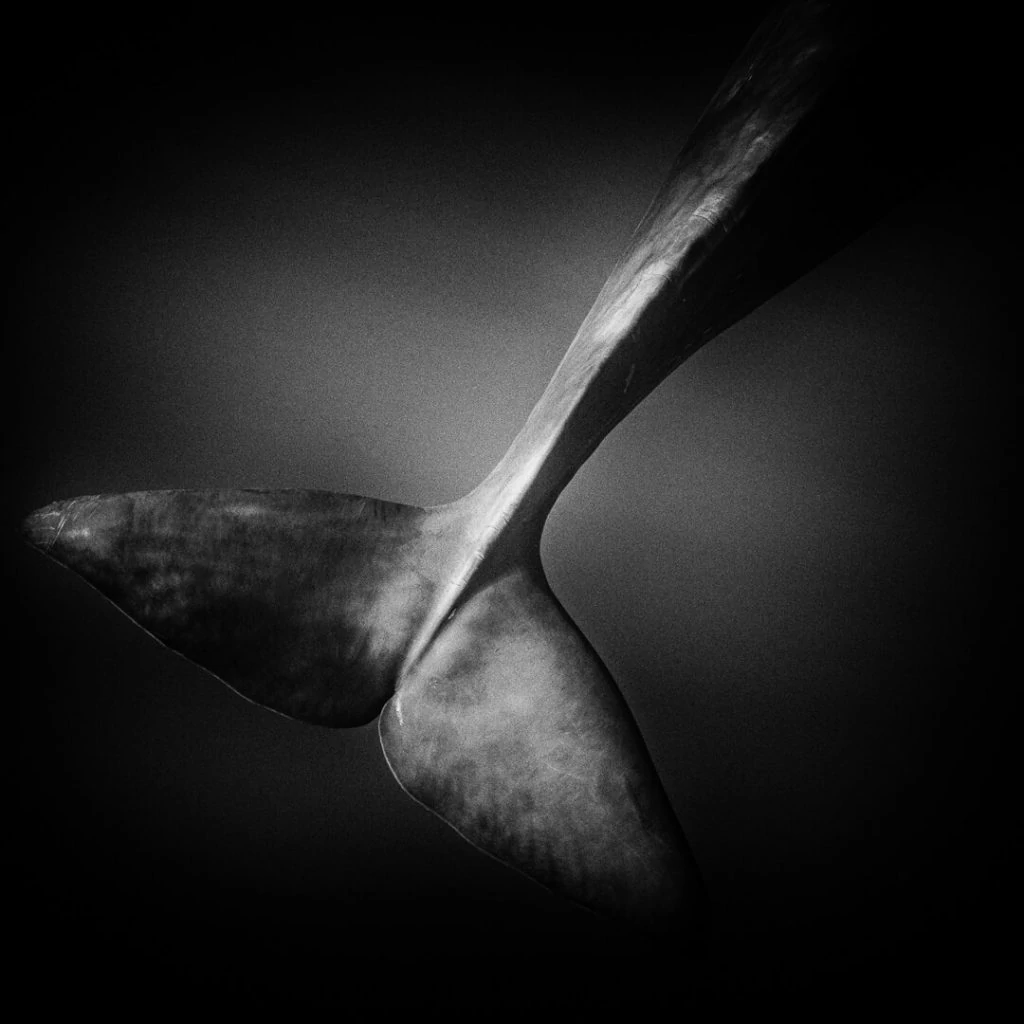

Wade was taking his first (sometimes homemade) underwater housings into the sea in the late 1960s and has done so ever since. But we started photographing whales together above and below surface back in 2005. We’re trying to illustrate and document as many aspects as we can of the lives of whales, particularly, sperm whales.

As much as we can, we attempt to move beyond documentary photography to create images that reveal some of the underlying aesthetic of the sea and these advanced beings that we call whales. To do all that that successfully we need images from above surface and below, and so working as a team works really well for us. As good as they each might be individually, given that whales are air breathing mammals, underwater and above surface images rely on each other to provide additional context and meaning.

What came first – diving or photography?

Photography.

What’s in your underwater photography kitbag?

We use DSLRs. Above surface, we use lenses ranging from 24mm and 35mm wide-angle out to 100-400 zooms, and very occasionally, a 500mm prime lens. Underwater, fish-eye and rectilinear wide-angles, out to 100mm short telephoto. Over the years, we’ve had a series of commercially available aluminium housings.

Favourite location for diving and underwater photography?

For sperm whales, it’s the Azores. The whale-watching industry there is superbly managed and regulated and we’ve been fortunate enough to be granted permits issued by the Azores Government. It’s illegal to swim with whales there without such a permit. These days we work there exclusively with Futurismo. We’ve swum with humpbacks in Tonga, but also gone looking for above surface images of them in Australia, Alaska, Norway and British Columbia. For coral reefs, Wakatobi in Indonesia.

Most challenging dive?

A better question might be, have there ever been any encounters with whales where photographing them has not been a challenge! That’s one of the joys of spending time in the presence of advanced beings with as wide an array of personalities, dispositions, moods and interests as you’d find in any crowd of humans. Add to that their immense size, the fact that they inhabit the hostile open ocean; the boat’s moving, the whales are moving, the camera is moving, underwater, even on the clearest of days there’s limited visibility, and the whales, almost without exception, prefer the up-sun position. That can all be a challenge!

Who are your diving inspirations?

Hans Hass, Ernie Brooks, and a couple of south Australians, Rodney Fox and Brian Rodger – who in the early 1960s both survived near-fatal great white shark bites and went back into the sea as soon as they were able and mentored youngsters, like Wade, along the way.

Which underwater locations or species are still on your photography wish list and why?

We’re always interested in new species, but when it comes to whales, our primary intent is to learn and record as much as we can about sperm whales. As Dr Richard Smith, an underwater photographer and marine biologist himself, has said recently: “The more you know, the more you see”. So, even though this is a hobby for us, we want to spend as much time as we can with these animals. The more we get to know them, the more we realise how little we know, and the more we start to observe and recognise subtleties and patterns in their behaviour.

What advice do you wish you’d had as a novice underwater photographer?

Underwater photography brings its own specific, mainly technical, challenges, but it would have been good to have been encouraged to first develop a sound grasp of why any particular photograph above water or below, or any particular work of art, resonated for us. Understanding the why, makes the what a lot easier to visualise and that in turn helps lay out a path for successful technical execution.

Hairiest moment when shooting underwater?

Nothing to do with whales. A quiet night dive on a coral reef suddenly shattered by a herd of white-lighting aliens. Turned out they were just a bunch of enthusiastic selfie-hunters.

What is your most memorable dive and why?

They’re not all memorable, of course, but too many of them have been to single any one of them out. Generally, any entry into the water that results in a meaningful insight into the power, scale, or complexity of the natural world beneath or on the surface, has to count as memorable.

Wade and Robyn Hughes

Wade and Robyn Hughes have won numerous awards for their work as underwater photographers. The duo are based in Australia and have a particular interest in photographing sperm whales. Check out their work at www.wadeandrobynhughes.com