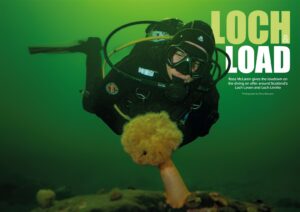

Marcus Greatwood specialises in freediving in remote, inaccessible areas, and on Kefalonia, he discovered a wondrous site affectionately referred to as ‘Muddy Hole’

I started freediving in 1999 and, although I’ve held records, competed in World Championships and coached hundreds of international-level athletes, exploration has always been my true reason to freedive. This passion to interact with the subaquatic environment has led me to breath-hold photography in order to share the beauty of the oceans that we can enjoy on a single breath

Freediving in hard-to-access locations has moved on in the past 20 years, and is now known as Extreme Location Freediving, with dedicated courses, clubs and regular expeditions.

Since the early 2000s, the NoTanx team have explored beautiful locations overlooked by most freedivers. We’ve developed safety techniques specific to this type of diving, as well as studying caving itself to extend our skills and catalogue of dive sites.

Underground lakes have now become some of our favourite spots; their amazing clear waters created by the lack of light and living organisms.

We began by exploring the cenotes on the Ionian Island of Kefalonia in 2016, returning twice a year since then – but nothing prepared us for the discovery at the affectionately named ‘Muddy Hole’ on the island in 2020.

Finding Muddy Hole

While researching the caves of Kefalonia, I had found an article in an Italian caving journal from 1990 with a tiny, detail-less map. Overlaying this onto Google maps, we had located several caves, including our Muddy Hole.

We had ignored this pretty uninteresting vertical shaft for a few years now, having only venturing into its entrance to practice some vertical caving at the end of another trip in 2020.

Abseiling into an unknown cave is quite a technical undertaking. It requires a lot of preparation – worst-case scenarios need to be anticipated. Even the first trip, which wasn't a freediving expedition, required a lot of specific equipment to be carried through the dense woodland and down a steep slope to the entrance.

The entrance leads to a 15-metre drop requiring an abseil, at the bottom of which a steep decline continues almost vertically to a dead end – a choke.

It was at this choke point where I sat for a few minutes waiting for the next person to finish using the rope when I noticed a small hole. Mat joined me shortly afterwards and he, not one to be shy of such things, squeezed through the hole as soon as he saw it. As we pushed through this tiny gap into the main chamber, we knew the 1990 cave survey had been misleading, if not outright wrong.

“Every inch of the ceiling is covered in thousands of razor-sharp limestone daggers, some stopping only inches from the water”

We had emerged into a huge chamber at ceiling height, quite literally covered in huge white speleothems (stalactites and curtaining) hanging down from the ceiling and walls up to eight metres high.

This truly was an amazing cave, visited by only a handful of cavers since 1970

but even more surprising was the lake of crystal-clear water at the bottom of the scree slope 25 metres below. It shone azure blue in our headtorches, leading off in both directions through heavily decorated tunnels and alcoves.

Our flight was booked for the next day, leaving us only the morning to attempt a dive. Not set up for extensive darkwater expedition, the preliminary dive was always going to be short, our summer wetsuits in the chilly 15°C water limiting our time in the water even further. Even so, this initial trip was truly awe-inspiring. We managed to identify four separate chambers, each more breath-taking and pristine than the last. A return trip was clearly necessary.

2021 expedition to explore Muddy Hole

In August 2021, a team of four divers and I to travelled to Kefalonia with the aim to not only explore but photograph Muddy Hole.

Rigging the access ropes is a complex process. The first rope runs continuously from outside the cave, to the top of the Main Chamber, followed by a second rope through the squeeze to the water’s edge. All the kit (freediving, photography and lighting) has to be meticulously packed before lowering to the first person waiting at the bottom.

It takes a full two hours to get from the entrance to the water’s edge. Wet-suiting up before the abseil, Mat and I knew what to expect, but the three girls experiencing it for the first time were truly stunned by the view that met them past the squeeze.

The Main Chamber is absolutely spectacular. I had shown several cavers our grainy photo from the first trip and they audibly gasped, definitely earning it the title of ‘worth a visit in its own right’. Despite the water looking inviting alone, the side channels that can’t be seen until you arrive at the water’s edge are even more enticing. The huge stalactites hang down into the water, guarding the entrances like a portcullis.

Our anticipation was palpable as we ditched our caving kit, donned our darkwater freediving apparel and slipped into the water. We knew these chambers could only be accessed with specialist training and although cave divers may have been able to enter through an underwater tunnel, each chamber has anti-scuba surprises of their own – we’re pretty sure we were the first people ever to enter.

The Amazing Chamber beyond the Portcullis is nothing less than jaw-dropping. Every inch of the ceiling is covered in thousands of razor-sharp limestone daggers, some stopping only inches from the water. Picking our way through, we had to be delicate and careful of our movements and we realised there is no way a scuba diver could surface in here – the crystal-clear water made it look like there is no head-sized gap between these intricate decorations.

Cave formation and calcite decorations

Speleothems (stalactites, stalagmites and curtains) form when ground water dissolves limestone rock when travelling through it by infiltration. As the water enters the air inside a cave, these dissolved minerals get deposited on the ceilings, walls or the floor. This process is gradual, taking countless water droplets to redeposit enough calcite to form just a single centimetre of rock.

Speleothems cannot form underwater as the ground water needs to become a droplet in air to deposit its mineral load. Thus we can deduce that although vast quantities of water formed these tunnels, the sea levels must have dropped, draining these caves for many thousands of years to allow the calcite formations to grow before the sea level rose again to flood the chambers as we find them today.

Inside the Main Chamber, the drapery (hanging speleothems) are metres high, which will have taken thousands of years to form. It is interesting that there are not many stalagmites (floor-standing formations) as this makes it evident that there must have been many ceiling collapses to break any formations here. A ceiling collapse like this is what will have opened up the entrance to allow us access to these deep caverns.

Calcite is pure white, only turning brown when contaminated with mud or when humans touch them, leaving an oily residue that cannot grow or regain its majestic colouring.

The White Room

The water level in these caves varies due to rainfall on the island, but not by much. The first time we entered, we saw a huge air-filled cavern beyond the initial chambers. At the time we had no way of knowing if the air was toxic or not, nor did we have time/equipment to dive along the flooded tunnel to investigate it.

On our returning visit to the Muddy Hole, the water level was about 30cm lower, revealing an air gap leading to The White Room. Although it was not big enough to breathe along its length, we knew the air on the other side was good.

This allowed us to freedive into the next chamber we had only glimpsed the first time we were here.

“Time was running out and we had to leave, but not before Muddy Hole gave us a tantalising glimpse of another huge chamber, fully submerged at the far end of The White Room”

We were genuinely shocked by the size of this cavern, lined with white decorations that almost glowed pure white (thus the name). This chamber was definitely not on the original cave survey. However, the air gap was only visible to keen-eyed freedivers when the water level was particularly low, so no sensible scuba diver would have surfaced here. This was another first entry to a new chamber.

Let’s get one thing straight – The White Room is huge. At least 30 metres long, eight metres high at points and 10m deep underwater. Freediving in the gin-clear water here was a unique experience. The beams from our powerful torches (thank you, Anchor Dive Lights!) peered off into the dark recesses beyond our vision. No light had entered this cave for thousands of years, yet we were able to see as clear as in a swimming pool.

Although the whole purpose of the expedition was to explore this one cave, we had only been able to penetrate this deep once during the week. Time was running out and we had to leave, but not before Muddy Hole gave us a tantalising glimpse of another huge chamber, fully submerged at the far end of The White Room. It was a huge white chamber 10m deep, a perfectly flat white roof and sheer white walls. Let’s be clear – we use huge 5K lumen cave diving torches, designed specifically for this situation, yet as their beams faded into the epic darkness, there was no end in sight…

The underwater camera had been packed away, and so the unnamed chamber remains unphotographed… until our next expedition to the Muddy Hole.

Photographs by Marcus Greatwood