Scuba Diver Q&A – David Strike, Part Two

With hundreds of articles under his belt, and a hand in organising various renowned diving events, David Strike is a veritable mine of information, with a diving history incorporating recreational, technical, military and commercial diving

Photographs by David Strike, Janet Clough and Jill Heinerth

You have written hundreds of articles about diving across various media – what is it about diving in general that still gets your creative juices flowing?

I’ve struggled with this question… more than any other. Probably because I find all aspects of diving – in all its forms – offers a rich tapestry of wonderful material covering the full range of experiences, from cutting-edge exploration in caves or open ocean to edge-of-the-seat drama, slapstick humour, or the Wow! moment when a novice first discovers the joy of weightless interaction with marine life.

All of them have their moments and all of them offer an exciting glimpse into an alien world. And all of them interest me. Sometimes it’s the technology itself – rather than the individual user – that stimulates my interest.

But more often than not, it’s the character and personality of the diver and, more importantly, their attitude that gets the ‘creative juices flowing’.

A more prosaic answer is to say that I still get a kick out of anything to do with diving that – in my view – is new and original; especially when it breaks free from any bureaucratic restraints, and that returns recreational diving to that period in its ascendancy during the 1950s, 1960s and on into the 1970s, when adventure was just a fin-kick away.

What is your best diving memory?

A fly-speck on the map, Addu Atoll and the island of Gan are located just below the equator at the southernmost tip of the Maldives, an island nation of 26 Indian Ocean atolls.

Established as a Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm landing strip and base during World War Two, Gan’s military significance remained undetected until late in the war when, despite the presence of anti-torpedo nets, the German submarine U-183 fired a long-range torpedo shot from outside the atoll at the tanker British Loyalty.

Although badly crippled the tanker did not sink and, once repaired, became a static oil fuel storage vessel.

In February 1965, one month shy of 21 years since the torpedo attack, the hulk was still a prominent feature of the lagoon, and while the Royal Air Force had, by this time, taken over military control of the island and its airfield and landing strip, RN vessels still regularly stopped over before the final leg of their journey to Singapore.

Shortly after anchoring in the lagoon, our small frigate received a signal from the Royal Air Force contingent based on the island requesting the services of a diver.

The immediate thought was that an aircraft had overshot the landing strip and crashed into the ocean; a salvage and recovery job to test the limits of diver training and add a degree of excitement to the routine of ship-board life.

Stories of sunken wrecks and the efforts to salvage their precious cargoes have always played a pivotal role in the development of diving.

Always regarding salvage diving as a noble tradition – and only too happy to briefly escape the cramped conditions of shipboard life -I was loaded into the ship’s cutter and ferried across to the jetty to be met by a welcoming party of RAF Officers and NCOs who briefed me on the task.

One of their number, an ‘elderly’ RAF sergeant, had apparently been among a small group sitting on the end of the jetty fishing. One of his companions had told a funny story that caused the sergeant to laugh so loudly that his false teeth fell out and plopped gently into the waters beneath the short pier.

My task was to recover the dentures… a less-expensive option than having him flown to Singapore for treatment and one that – if successful –would, I was assured, earn me a crate of beer.

“I had survived another scare and added to the sum of my knowledge about diving safety and the mechanics of fear”

Almost immediately finding the teeth nestled into the sand at a depth of about 5m – and very mindful of the fact to never make diving recovery jobs look easy – I decided to go for a swim among the coral heads before surfacing.

It was my first dive into the gin-clear waters of a tropical coral reef.

Surrounded by thousands of darting reef fish and facing a living wall of shimmering barracuda waiting just beyond the edge of the shallow reef, the richness of life, the vivid colours and the brilliance of the light were everything that Jacques Cousteau’s television and film documentaries had promised about diving… and that I was seeing for the very first time.

Although I’d set out prepared to ‘seize the depths’ rather than the teeth, it was such an intense experience that I almost forgot about the beer… almost.

On the flipside, what is your worst diving experience?

In 1972, I was trapped at a depth of a little over 36m inside the 38-inch diameter leg of a fixed-platform drill rig being erected in the southern part of the North Sea. The platform’s base had been towed into position on a large, purpose-built construction barge.

Valves allowing free flooding of the legs were opened and the entire structure tilted and, with the aid of the barge’s heavy-duty crane, settled into an upright position on the seabed.

The conical plugs sealing the bottom of each leg would then be removed and pilings driven down inside the legs to firmly anchor the platform in position.

Removing the conical sealing plugs should have been a straight-forward task. Each plug had a heavy chain shackled to its top with a wire hawser crimped onto the chain’s free end.

These hawsers passed up the entire length of each of the eight legs and ended in an eye-splice that could be easily attached to the crane’s hook. In a perfect world the crane would then haul up the plug and clear the way for the anchoring phase of the operation.

That it’s not a perfect world became evident during the process of ‘pulling the plug’ and the discovery that none of the wire hawsers had been properly secured to the chains.

A disaster that meant either an extremely costly attempt to refloat the platform and a return to the construction yard, or sending down divers to try and retrieve the situation by re-attaching the wire hawsers to the chain.

The company tasked with carrying out all of the construction barge’s diving requirements had declined the job on safety grounds.

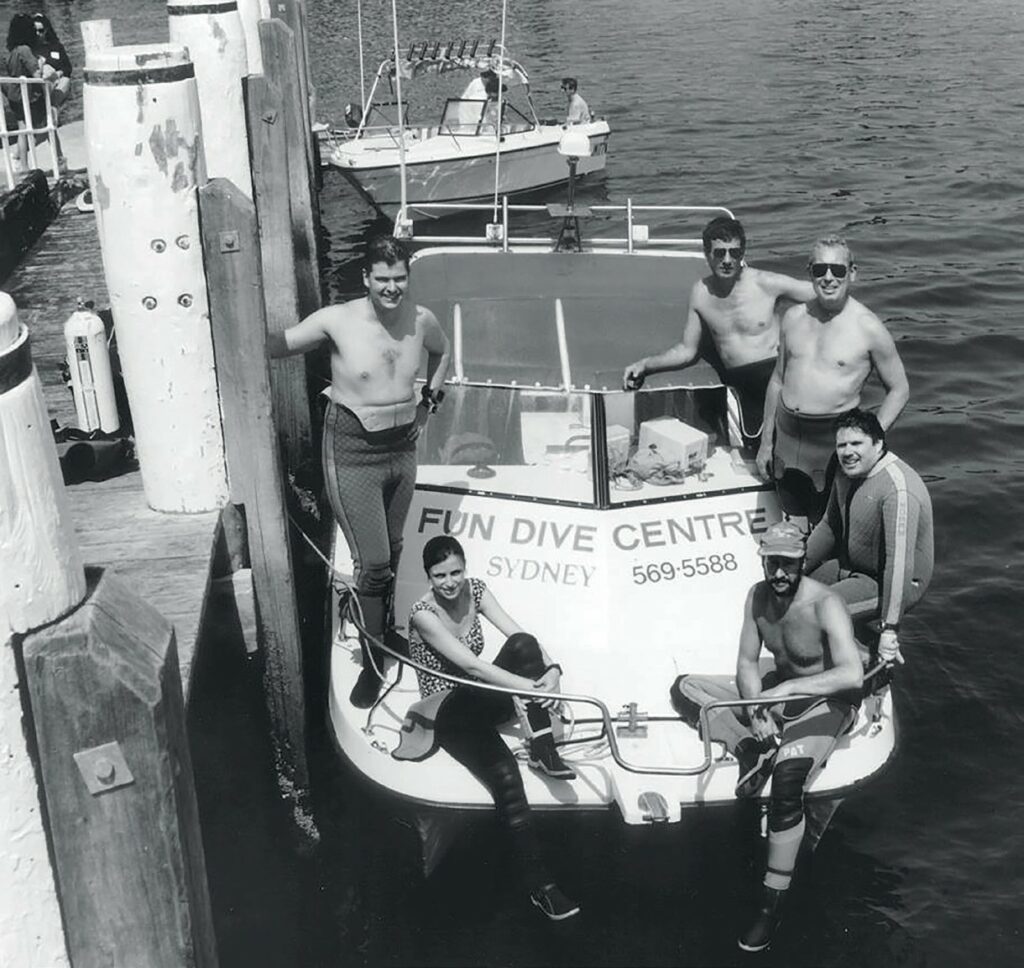

Although we were contracted to a competitive oil exploration company, our five-member dive team – two former SBS Royal Marines, one former Para (the nominal ‘Diving Supervisor’) and two former Royal Navy sailors – were working in a nearby sector just a short helicopter ride away.

We received a radio plea for help… and offered a huge cash inducement for what appeared to be a seemingly straightforward task. We agreed, and – with eight legs requiring attention – drew straws to see who would dive twice and earn a greater share of the bounty.

Each leg was accessed along what would, on the completed platform, be the lower catwalk.

We were then required to climb three metres or so up one side of a rope ladder slung over the open top of the leg, negotiate the lip, climb down the inside of the flooded leg to the water’s surface, and then – while firmly grasping a loosely fastened shackle now firmly attached to the business end of the slack wire hawser – descend to the cone-shaped plug, retrieve the chain, attach it to the hawser with the shackle, ascend, climb up the inside ladder, clamber over the lip, and then climb down the outside of the ladder back on to the catwalk; all of which would be performed within the no-decompression time limits and while – because of the problems of effectively deploying an umbilical surface demand hose – wearing twin-cylinders.

In those days the concept of redundancy was considered an unnecessary extravagance. We used a single regulator attached to the manifolded twins. BCDs were not even on the horizon of our thinking. Instrumentation was limited to a watch with rotating bezel set to the start of the dive.

Fins were redundant in the tight confines of the pipe and, given the nature of the task, hand-held lights were equally superfluous.

The first leg went without a hitch. I took the second leg. Having negotiated the climb up and down the rope ladder to the water’s surface inside the leg, I took a firm hold on the shackle and wire, and – with ambient light restricted to the small opening at the top of the leg before being filtered through a thick layer of oil – quickly sank into total darkness.

Feeling my way down the narrow tube, I eventually came to rest on top of the cone-shaped plug. Unable to bend little more than a few inches either forward or backward without either my head or the cylinders coming into contact with the circular 38-inch diameter walls of the leg, I began to straddle the cone in order to properly reach the chain.

Reaching down between my legs, my hand brushed against the chain and dislodged the heavy links from their perch. Before I could grab hold of any part of the chain, the heavy links tumbled down into the sloping gap between the tube’s wall and the plug, firmly trapping one of my legs.

After unsuccessfully struggling to free myself and only succeeding in over-breathing the regulator, I quickly came to the realisation that I was stuck.

Because of the equipment choice – and the belief that it was to be a quick and straight-forward task – we had no communications system that I could use to inform those back on the surface of my predicament.

Attempts to haul my legs free of the entrapment by pulling myself up the hawser were thwarted by the fact that we had purposely left the wire free running. Pulling on it would only add to my woes by bringing coils of slack wire down around my shoulders.

Trapped in the pitch blackness and with the knowledge that it would be some while before those on the surface became aware that there might be a problem – and who, even then, would probably be unable to do much to assist -I struggled to quell a rising panic.

Bringing my breathing rate back under control, I managed to pull one of my legs free of the few links that had settled on that side of the plug.

With the combined leverage provided by pushing against the side of the cone-shaped plug with my free leg and pressing downward with my hands against the walls of the tube I was, for short yo-yo bursts, able to ease the pressure on the trapped leg and, by wriggling my foot, gradually ease it free of the bulk of the chain to the point where I could eventually reach down and grasp the links.

A process that – judging later by the time spent underwater – probably took less than 20 minutes but that seemed to take so very much longer.

Slowly feeding the chain through my hand, I kept a firm hold on the final links while carefully feeling for the hawser and shackled end with my free hand.

With fingers that were now puffy and softened by the water and the cold, I managed to secure the shackle to one of the chain’s links and the job was finally complete.

All that remained was the ascent, an extended seat-of-the-pants decompression stop (our one concession to safety had been to rig a short, weighted line attached to the lower rungs of the rope ladder with decompression stops down to the 9m mark indicated by knotted pieces of hessian sacking) followed by the climb back up the rope ladder and down the other side to the safety of the catwalk.

I had survived another scare and added to the sum of my knowledge about diving safety and the mechanics of fear.

What does the future hold for David Strike?

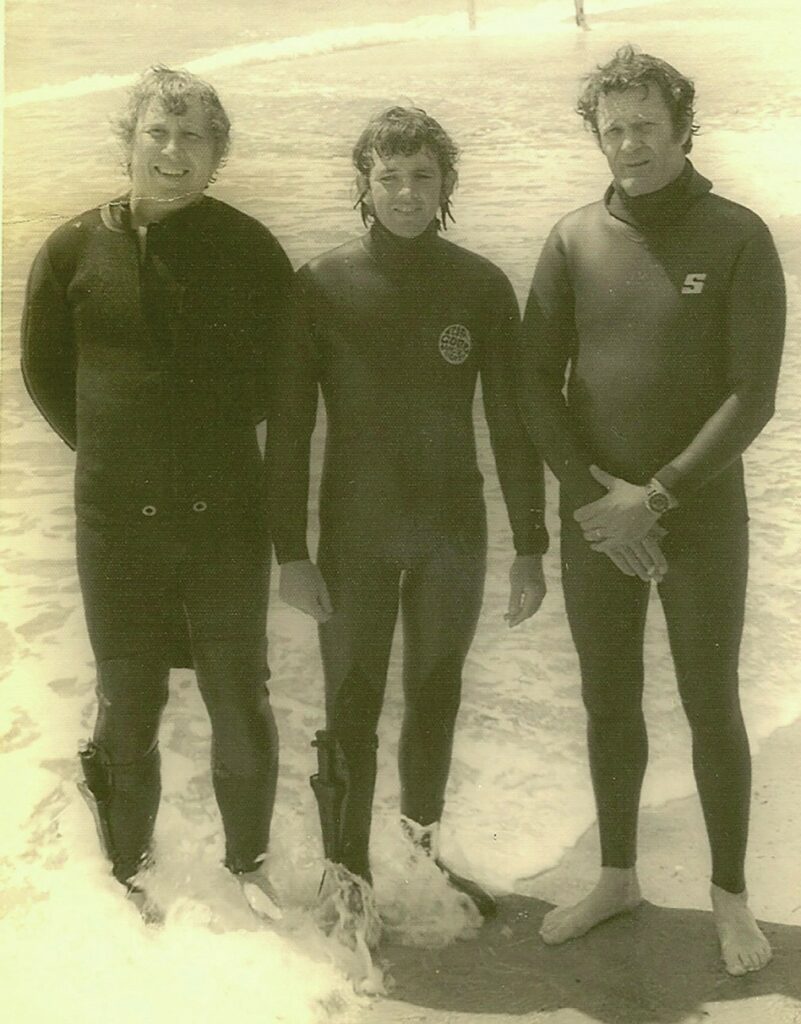

I have become – in recent years – more aware of the importance of family and the enormous debt of gratitude that I owe to them all for the patience and regard that they’ve always shown to me… and the love. I met Sylvia while on weekend leave during my Navy diving course.

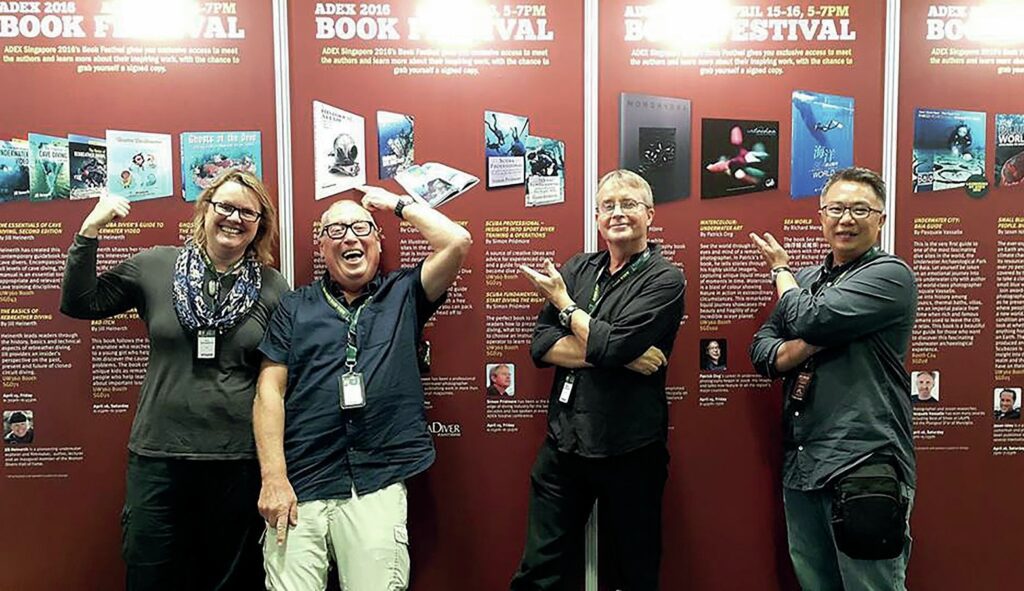

I’ll continue to dive for as long as health permits. I still have one or two more diving events that I’d like to have a hand in organising; I have a book or two based on modern diving history – and the personalities involved in its growth – in the offing; I have an on-going interest in the growth and development of diving through industry bodies; and – as far as possible – I hope to enjoy occasional social catch-ups with diving friends whose stories and exploits are worth recording for posterity.

I live close to the sea and can hear, as I close my eyes each night, the sounds of ocean breakers crashing on the shore. And again, on waking each morning.

Life, in short, has been very, very good to me. And so much of it has been directly due to the people that I’ve been privileged to meet through diving. As for the future? Knowing what is, with each passing year, looming closer, I’m not in any hurry to meet it head on.

CUSTOMER TESTIMONIAL

“KUBI Dry Gloves are our first choice for the most-reliable cuff system on the market. Streamlined, simple, dependable and reliable. We’ve dived them across the world on some of the biggest, deepest wrecks, walls and beyond“

MATT MANDZIUK | DAN’S DIVE SHOP, INC. | ONTARIO, CANADA

This article was originally published in Scuba Diver UK #76.

Subscribe digitally and read more great stories like this from anywhere in the world in a mobile-friendly format. Linked from KUBI Dry Glove Systems