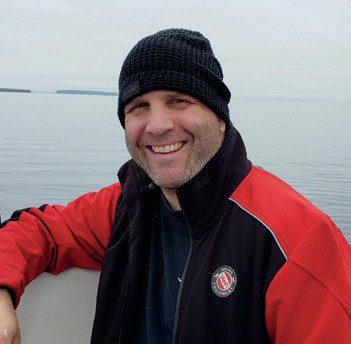

Q: As we normally kick off proceedings, how did you first get into scuba diving?

A: Growing up in a post-World War Two family with strong Naval connections (my paternal grandfather had served as a Royal Navy submariner during World War One; one of his two sons, my Dad’s younger brother, was a commercial diver involved in salvage operations, and on the other side of the family – for the most part, Royal Marines – was another relative, one whom I’d never met, but who was apparently something to do with diving), the stories overheard at family get-togethers were, invariably, those relating to the Senior Service, their seaborne operations, submarines, shipwrecks, salvage, and diving… and ‘frogmen’, a snappy, media-inspired title bestowed on those free-swimming divers involved in some of World War Two’s more-audacious underwater combat operations.

In the late 1940s, one of my Dad’s friends, a Chief Petty Officer based at HMS Excellent, the Royal Navy’s Gunnery School at Whale Island, invited us to visit him in Portsmouth and view one of the first post-war ‘Navy Days’; an annual PR exercise in which, over several days, the public were given an opportunity to take tours of Royal Navy vessels and view simulated action displays.

I still have several distinct memories of that visit to HMS Excellent: the most vivid being a visit to Portsmouth’s Royal Naval Dockyard where, standing on the side of a flooded dry dock, I watched pairs of divers, dressed in sleek rubber suits and wearing oxygen rebreathers, straddle the backs of large, torpedo-shaped, machines – dubbed ‘human torpedoes’ by the popular press – that they guided beneath the oily green waters in a simulated demonstration of an attack on enemy shipping.

It was the beginning of a lifelong fascination with divers and diving. One that included a brief flirtation with a local branch of the British Sub Aqua Club before joining the Royal Navy.

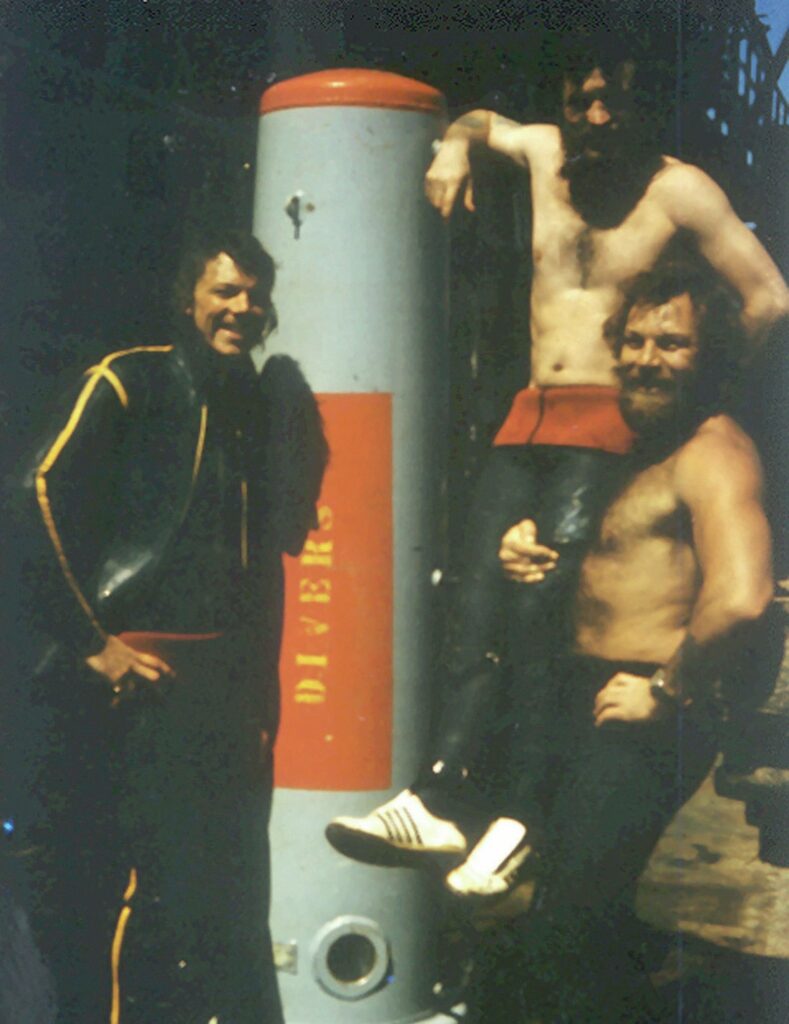

Completing basic training and assigned to my first ship, still under refit before sailing for the Far East, I responded to a message placed on the ship’s Notice Board calling for volunteers for diving duties – it was on the cusp of the change-over from O2 rebreathers to open-circuit apparatus – for the Navy’s four-week entry-level Ship’s Diver course, then held in the Diving School at HMS Drake, the Royal Navy Barracks and dockyard in Plymouth.

It was a course with a high failure rate, previous applicants returning after a few days, or a week or so, with tales of hardship and horror that obliged them to voluntarily withdraw from the course. I immediately put in a request form to be considered for acceptance – this was, after all, one of my reasons for joining the Navy – and was summoned to an interview with the ship’s newly appointed Diving Officer, who approved my request.

At 18, with my draft papers clasped in my hand and kit bag over my shoulder, I presented myself to the Chief Petty Officer Clearance Diver in charge of the Diving School at HMS Drake.

“What’s your name, lad?” He asked.

“Strike, Chief.” I replied in a wavery voice.

“Strike, eh? I’ve got some relatives called Strike. What’s your father’s name?”

“Billy – Imean, William -Chief.” I nervously replied. “Billy, eh? I’m your Uncle, lad. You will pass this course.”

This, of course, is the sort of thing that all young recruits like to hear. At that point – and I gladly confess to mistaking what he intended as an order, as a statement of fact – Ididn’t know the meaning of the word ‘nepotism’, but if I had, I would have seen nothing at all wrong with it.

Needless to say, there was a downside. When the Petty Officers and Leading Hands conducting the day-to-day training heard that I was related to the Chief, I became an involuntary ‘volunteer’ for additional swims and exercises. And while there were times when I almost withdrew from the course, I was too afraid to fail. Of the close to 30 volunteers that had started the course, five of us passed. It marked the start of a long and on-going learning curve about diving… and one filled with many memorable episodes.

Q: You have got a mixed bag of diving experience, ranging from recreational and technical diving to commercial and even military diving. Which have you found the most challenging?

A: That’s a rather difficult question with no simple or direct answer. Certainly, the most economically challenging would have to be – in my case – technical diving because of its affordability. Rarely offering any financial return, the costs involved in technical diving – in terms of equipment, training and gas – can be prohibitive (And possibly lead to its acceptance as some sort of elitist category of diving… which it is not).

However – and again because of economics – occupational diving has its own share of challenges. Not least being the complexity of a task, the time required to complete it, and environmental considerations.

While recreational and technical divers have the luxury of being able to call a dive if conditions are less than perfect, occupational divers constantly face the prospect of losing a contract to a competitor if they consistently fail to complete a job on time… regardless of environmental factors.

I should also add that those two examples lose sight of the fact that distinctions between occupational diving and technical diving are sometimes – and increasingly – being blurred by the fact that while technical divers are not subject to the same strict standards and regulations that govern occupational diving in many parts of the world, they often – through sponsored, or self-funded programmes – carry out tasks that were once regarded as being ‘commercial’ in their scope.

CUSTOMER TESTIMONIAL

If, however, the extent and quality of the training is taken into consideration then the military wins… by a mile. Far too few – if any – recreational/technical training organisations have either the expertise, or the time, to properly train a person as a diver to that point where the requisite life-saving skills are impressed into ‘muscle-memory’ and become an automatic response to a situation.

And the training for the military is long, hard, and not based on the personal profit motive. Consequently, people fail the course. Something that seems to happen but rarely in the fast-food philosophy common to many commercially driven recreational training organisations.

Q: You are qualified on various rebreathers as well as well-versed in open circuit tech diving and have a raft of certifications from agencies such as PADI, SSI, BSAC, IANTD and ANDI. What is it that draws you to technical diving?

A: I’m always hesitant about use of the word ‘qualified’. Far too many people in diving are convinced that the terms ‘certified’ and ‘qualified’ mean much the same thing. They don’t. At a personal level, I view both as being at opposite sides of the diver training spectrum. While it’s true that I have first-hand experience of four rebreathers, I regard myself, by any standard, as being ‘certified’ rather than ‘qualified’. Patience is now no longer one of my virtues; and to my way of thinking – given the necessary time spent in pre-dive checks and post-dive maintenance – patience is an absolute essential when it comes to rebreather diving safety… as is constant practice and regular and recent use of the machine.

It seems to me that, in many instances, certification cards with no expiry date become, for many divers, an end in themselves and cheapen the value of a technical diving qualification… but that’s a whole other question deserving of lengthy debate!

However – and to answer the question – as Billy Deans, one of the acknowledged pioneers of technical diving, said in 1995: “Technical diving is… a philosophy, a mindset. Everything you do is based on making that dive absolutely perfect because if you don’t account for all of the parameters of the dive, you could get killed. It’s a constant vigilance that wears on a human being. To do it well you have to live, eat, breathe technical diving.”

It’s that commitment to excellence – the striving for perfection, if you will – that deserves to be front of mind for all divers, regardless of whether they’re from the military, occupational, scientific, recreational or technical sectors.

It’s one that seems to be more generally evidenced by a relatively small number of ‘technical divers’; those whose over-riding interest is in pushing back the boundaries of human knowledge. Rather than regarding the necessary trappings and equipment associated with technical diving – as well as the certification card – as being an end in itself, this small – and to my way of thinking, elite – sub-group (most of whom, by the way, have been speakers at events with which I’ve been involved) regard technology as the bus that will get them to where knowledge ends and discovery begins.

It’s the passion and commitment shown by this small group that I find inspirational… and the one that appeals to me the most about this facet of diving.

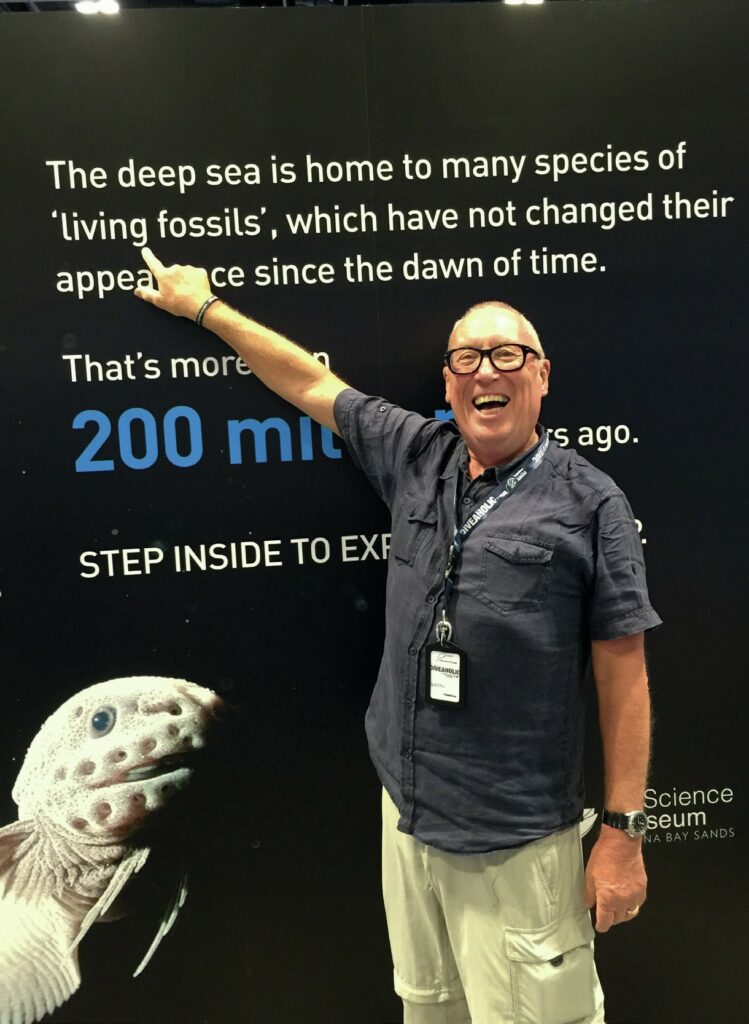

Q: You are a Fellow of the Explorers Club of New York. What is it about diving exploration that fires your imagination?

A: In 1923, when asked why he wanted to conquer the then unclimbed Mount Everest, the British-mountaineer George Mallory simply said, “Because it’s there.” It’s a seemingly trite statement, but one that’s packed with meaning for everyone who’s gazed at the ocean’s surface and dreamed of what might be.

While still at school, the physics teacher made the following comment in one of my annual report cards. “This boy lacks an imagination.” When it came to having an interest in science and its role in understanding the practical world, he was absolutely correct in his assessment.

However, as soon as I took up diving, my interest in physics – and other branches of science – received a wake-up smack around the back of the head. Discovering how little was known or understood about the effects of pressure on the human body, or how oxygen, the gas essential to life, becomes toxic when breathed at relatively shallow depths, stimulated the desire to learn more.

What did – and still does – surprise me most about diving is how little public funding diving research receives when compared with, for example, space exploration. Men have walked upon the surface of the moon.

But despite diving’s growing popularity we’ve progressed very little in our exploration of ‘inner space’ – the oceans of the world – or in having a better understanding of their importance in ensuring our continuing quality of life.

And this is, perhaps, where technical diving really comes into its own. The ocean depths are a huge laboratory where visionaries, like Bill Stone, can trial Autonomous Underwater Vehicles of his design that can also be used in the remote exploration of planets and worlds beyond our own: where researchers like Richard Harris can trial the safe use of hydrogen as a diluent gas for deep diving: where filmmakers, like James Cameron, can harness technology to reach the deepest ocean depths; or engineers, like the late Phil Nuytten, can create one-atmosphere diving suits for use in deep ocean exploration.

And where even the humblest diving ‘citizen-scientist‘– with no formal scientific training – is able to add to the sum of human knowledge.

Exploration is that urge to look into the unknown. In that regard, everyone who dives, whether or not they realise it, either is – or has the potential to be – an explorer.

This article was originally published in Scuba Diver UK #75.

Subscribe digitally and read more great stories like this from anywhere in the world in a mobile-friendly format. Link to the article