Diatoms, which are microscopic algae that would have raised little or no attention years back, have now become a focus in aquatic forensics, opening doors to new investigative possibilities. These organisms have the potential to be useful in a variety of aquatic investigations, as Kelly Ann Moon explains.

Diatoms can: Aid in the diagnosis of cause of death; help estimate the post-mortem submersion interval – the PMSI – to be explained below; help identify where the decedent was in water if the body was perhaps moved by the offender; and link possible suspects or evidence to the scene.

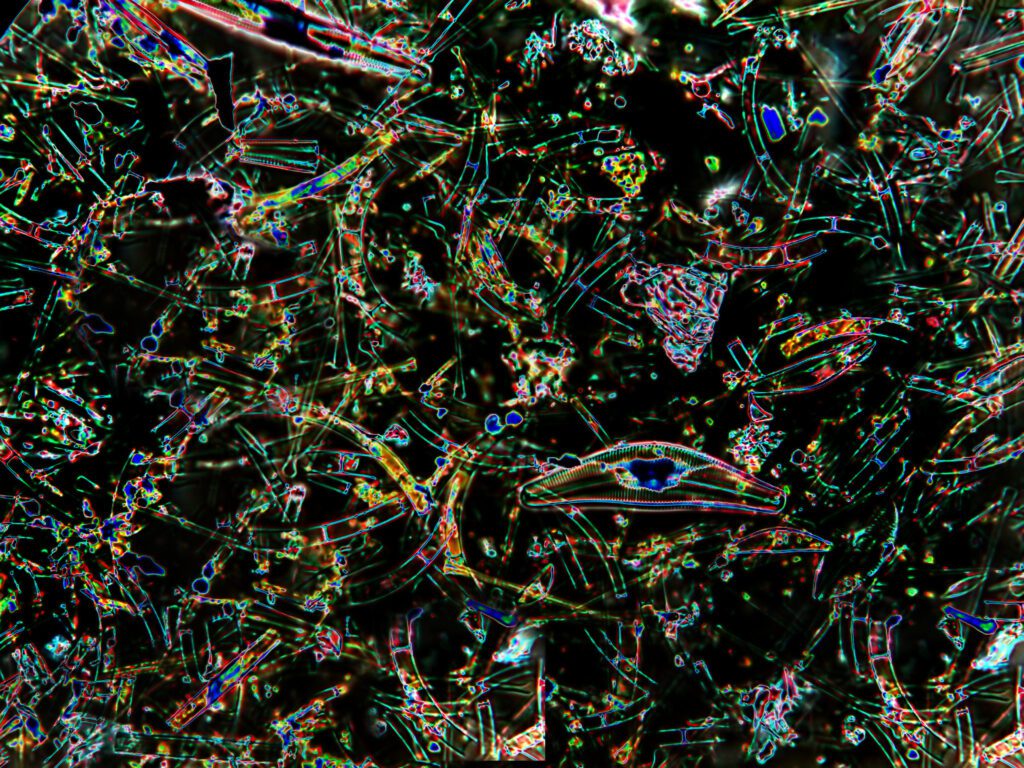

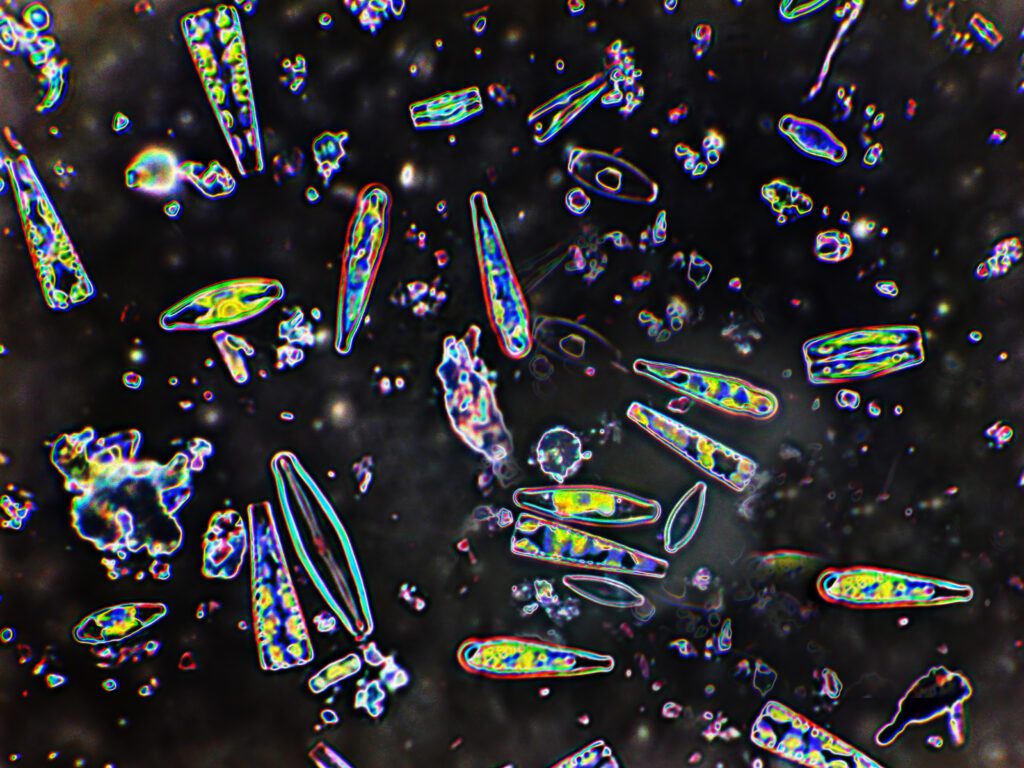

But what are diatoms? They are classed under Bacillariophyta and are unicellular plankton algae (phytoplankton) that reside in most fresh and salt environments. Many different taxa of diatoms can populate one body of fresh, salt, or brackish water and are identified by the hard silica shells called frustules that encase them.

Frustules, which are often quite beautiful, are strong enough to be preserved in sediments for thousands of years, even after the organisms themselves have died, and it’s therefore this hard shell that can be useful when analysing evidence.

These organisms are photosynthetic; requiring them to live in water or damp environments exposed to sunlight such as oceans, lakes, rivers, streams, soil deposits and can even be found in the mud in an average backyard. As fossils, they are also known as diatomaceous earth, and are commonly used in abrasives, paints, fertilizers, insulation, and filters.

There are thousands of different taxa of diatoms and as many as a hundred can be in a given environment at a specific time. Different taxa can vary by size, shape, and living environment.

Aiding in diagnosis of cause of death

Diatoms can be sensitive to environmental variables such as pH, seasonal variation, and different bodies of water, resulting in different populations of diatoms for every body of water. For example, some diatoms prefer living attached to the substrate of shallow, moving water areas such as creeks, while others prefer deep lakes. What this means forensically is that a diatom expert is able to link evidence to a type of water: freshwater, shallow creeks, or ocean environment. This does not, however, mean that diagnosis is an easy process.

Misconceptions about testing and drowning – The diatom test for drowning has been used in the past but is often misunderstood, resulting in many investigators considering the test useless. This is how the misconception arises: The test looks for diatoms in lungs, spleen or bone marrow. The conclusions in the past have been that if diatoms are found, the cause of death is deemed to be drowning, and if they are not found, the decedent didn’t drown. Neither of these conclusions is correct.

In fact, new evidence shows that diatoms can be found in the tissues of decedents with no history of drowning, and not all drowning victims test positive for diatoms. The question, therefore, is not whether or not a cadaver tests positive for diatoms, but rather whether the quality and quantity of diatoms found in the decedent match the population of taxa of diatoms in the aquatic environment in which the body is found.

In addition, were the tissues that tested positive granted protection from possible post-mortem diatom ‘contamination’ caused by water entering the body’s open cavities, such as the abdominal cavity. For example, the spleen can be easily contaminated. However, femur bone marrow is more protected than the spleen or the lungs. The supposition is that for a diatom population of the drowning medium to match the bone marrow, the decedent had to have inhaled water that contained diatoms.

The diatoms then travelled from the lungs to the pulmonary capillaries, to the left side of the still beating heart, and to the bone marrow tissue. Similarly, if the diatom test is negative, then one cannot exclude the cause of death as drowning, since not all drowning victims inhale a sufficient concentration of diatoms, or the diatoms may not reach the tested tissues, since not all drowning victims inhale a sufficient concentration of diatoms. Testing samples from the skin, lungs, or muscle can contain diatoms from post-mortem exposure, and so may also create a false positive reading.

In summary, there are many variables to consider. Even with these misunderstandings or false readings, the diatom test can be a crucial aspect of an aquatic investigation if analysed correctly.

Drowning as a problematic diagnosis – Drowning is the ‘process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion/immersion in liquid' according to the WHO. Unfortunately, drowning is a diagnosis of exclusion. There is no universally accepted medical test for drowning, since drowning is hard to detect.

Common findings that suggest drowning as a cause of death are froth of the mouth and nostrils, lung emphysema and edema, and pleural effusions. However, these findings are not exclusive to drowning cases and may not even appear in a victim who has drowned. Another problem arises in the diagnosis of drowning when the body is rapidly putrefied, which is common in warm waters.

The physiological basis for the diatom test is as follows:

When a victim inhales diatom-filled water while they are drowning, diatoms can perfuse through the alveoli into the blood stream. The blood, which now contains diatoms, then circulates throughout the body, reaching peripheral organs and tissues. So, if diatoms are found in distant organs or closed systems, and are of a great abundance, the cause of death is most likely due to ante-mortem drowning.

When performing a diatom test, the ideal sample would be obtained from the bone marrow inside the femoral bone, which is a closed system. The only way diatoms would be able to enter the bone marrow is when the heart is still pumping. If the victim was dead before he or she entered the water, it is unlikely diatoms would be able to circulate throughout the body and make their way into the bone marrow. A positive diatom test from the bone marrow most likely indicates an ante-mortem drowning.

Furthermore, the diatom test can aid investigators in determining a cause of death even when drowning is not directly evident in the circumstances in which the body is discovered or from autopsy results. For example, if a body was discovered nowhere near a body of water, or even charred beyond recognition, the diatom test can be of great assistance.

Testing for the post-mortem submersion interval (PMSI)

One of the most important questions asked in a death investigation is time of death. If no one saw the person die, investigators have to use other means to estimate this answer. In aquatic cases, specifically, post-mortem submersion interval, the time the body was immersed in water, is extremely helpful because a body may not resurface after a period of time so date and time of death can be very uncertain. Determining this time can be important piece of evidence. A body never lies.

If a suspect’s story does not match up with the body’s PMSI, the suspect may not be revealing the full story. So, the second use for the diatom test would be determining the PMSI. This test is often used in terrestrial environments, and then flesh-eating insects, such as blowflies and larva produce evidence. In water environments, algae, including diatoms that are associated with cadavers, allow investigators to better estimate the post-mortem submersion interval. The combination and abundance of algal species found on these nutrientreleasing carcasses may be useful to investigators, and these variations can be directly correlated to the amount of time a body spends in the water.

To determine the post-mortem submersion interval (PMSI), an investigator must define which of the five stages of decomposition are being shown: submerged fresh, easy floating, floating decay, advanced floating decay, or sunken remains. By combining these observations with the analysis of diatoms and algae species, investigators will be able to better determine PMSI.

Pinpointing the location the body entered the water

Not only will studying diatoms allow investigators to know the diagnosis and PMSI of a victim, but they can also be used to pinpoint the location where the victim could have been drowned or dumped. The ability to determine this is because every body of water possesses its own unique species and abundance of diatoms. Using diatoms to determine the location where the body entered the water is also used to link suspects and evidence.

Linking the suspect

By determining the location where the body entered the water, scientists can match that sample to diatom samples tied to the suspect. There have been cases that found diatoms on a suspect’s clothing, car, or shoes; those samples were matched to the samples found on the body, showing the suspect was in the same location where the body entered the water.

Commonly used test – There is not one general method used to perform a diatom test. The scientist elects the method based on his or her own expertise. The most common approach used today is the acid digestion method. Although there are many variations to this method, the general test involves dissolving the sample in acid; nitric acid being the most globally accepted acid for this test. Acid is added to the sample and heated, usually for about 48 hours, until the sample is dissolved. The liquid is then cooled and placed in a centrifuge, a device that spins a liquid to separate the contents. The separated material is examined.

Because there is not a standard protocol for the performance of a diatom test, the results can differ greatly. The qualifications of an idyllic diatom test would be: a quick, simple digestion process that produces limited damage to diatoms and other phytoplankton; minimal organic residue; inexpensive reagents that are able to digest the diatom frustules without destructive, and devices that are originally diatom free. Even with less than flawless tests, a diatom test can assist in many different aspects of a drowning investigation, if read properly.

The Blind Test – Because of its mixed reviews, the diatom test can be extremely controversial in the courtroom. In order to positively perform an unbiased diatom test, a blind test needs to be conducted: the person performing the final stages of the test should not know which samples came from where.

A hypothetical example of this strategy would be if a department wanted to try to match diatoms found on a suspect’s clothes to the pond where they dumped the body. Six possible samples are provided: 1) diatoms from the suspect’s clothing; 2) diatoms from the lake where the victim was drowned; 3) the bone marrow from the victim; and three controls such as 4) another body of water nearby; 5) water from a sink; 6) water from a water bottle. The controls do not have to be the same every time, there just needs to be samples that are not related to the case to reduce biasness. All six of these samples are placed in identical jars, with labels that the scientist performing the test would not understand. The scientist then determines that jars 1, 2, and 3 all match, however the origins of the samples are still unknown.

In summary, these microscopic algae have been important tools in the four ways we’ve discussed. However, the diatom test must be conducted and read correctly. If used properly, diatoms can significantly alter aquatic death investigations.

Andrea Zaferes running UK workshops in July

If the above article caught your interest, you will be pleased to hear that world-renowned drowning expert Andrea Zaferes is coming to the UK in July to run a series of interesting and informative workshops, courtesy of The Diver Medic.

She began teaching diving with Dr Lee Somers and Karl Huggins at the University of Michigan’s Scientific Diving Program, and then served as a Diving Safety Officer for the American Museum of Natural History’s Animal Behaviour Research Department, having three research papers published by the age of 22.

She took her first diving rescue course at age 16 with Walt Butch Hendrick, and since that time has become Vice President of Lifeguard Systems Inc and RIPTIDE Inc, a Course Director and instructor trainer, a well-published author, a noted public speaker, an award winner, a programme designer, and one of the leading trainers in the international water rescue and recovery industries today.

Andrea teaches hundreds of police, fire, EMS, military, and USCG personnel annually throughout the US, Canada, Asia, and the Caribbean.

The workshops include Aquatic Abuse, Death, and Homicidal Drowning Investigations training, which is ideal for; law enforcement, dive teams, death investigators (coroners, forensic pathologists, etc), child abuse physicians, domestic violence workers, and prosecutors. If you would respond to, or investigate, an aquatic incident from bathtubs, swimming pools and toilets, to rivers, lakes and ponds, then you will find this course very valuable.

To show your interest, email: info@thedivermedic.com

Other workshops she will be conducting include the art of being a great Dive Leader, Sports Diving Contingency Plans, and Field Neurological Evaluation and Oxygen Administration.

Photo credit: K-Kwan Kwanchai, Jubal Harshaw, Michael Taylor and Brian Goodman

Article courtesy of Code Blue Education