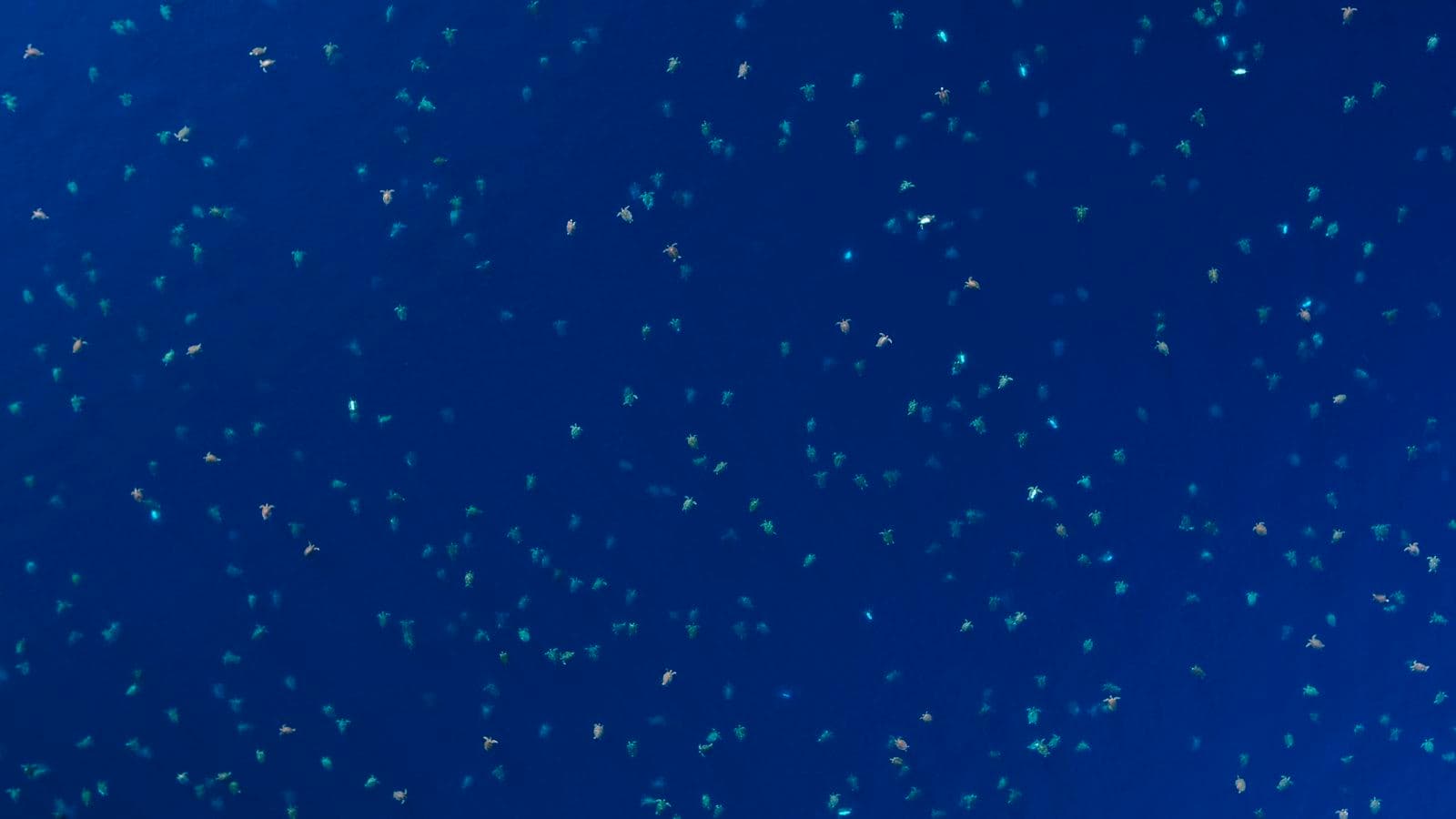

There are 640,000 more endangered baby turtles on the Great Barrier Reef thanks to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation and its partners

Thanks to the Raine Island Recovery Project, the globally endangered green turtle is now fighting back.

Since the project’s inception five years ago, led by the Great Barrier Reef Foundation and its partners, it has delivered 640,000 turtle hatchlings to the Reef, in addition to saving more than 600 turtle mothers. Millions more hatchlings are expected to emerge over the next decade thanks to the project’s efforts.

90% of the Reef’s entire northern green turtle population comes from Raine Island, a vegetated coral cay approximately 620 kilometres north- west of Cairns. The population was steadily declining due to nests being flooded, eggs drowning and fewer hatchlings surviving the harsh tides. In response to this concerning decline, the project has:

- Delivered 640,000 extra turtle hatchlings to the Reef as a direct result of the Foundations project

- Saved 696 turtle mothers

- Doubled the nesting area at the world’s largest green turtle nursery

- Installed 1750m of protective fencing

- Moved 40,000m3 (equivalent to 16 Olympic-sized swimming pools) of sand to raise thenesting beaches

- Reprofiled 35,000m2 of beach sand

- Doubled the nesting area above tidal inundation from 35,000m2 to 70,000m2

- Flipper-tagged around 8,000 turtles and satellite-tagged 45 adult female turtles, providing vital intelligence about their movements and behaviours to help protect the speices

The Raine Island Recovery Project was the first large scale adaptive management project on the Reef. Brought together by the Traditional Owners of Raine Island – Wuthathi Nation and Meriam Nation (Ugar, Mer, Erub), Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and BHP, it ensures a stable future for the Reef’s green turtles and the island’s vital ecosystem.

Anna Marsden, Great Barrier Reef Foundation Managing Director

“Nowhere on the planet do more green turtles come to nest than Raine Island which is why it’s so important for us to do everything we can to ensure a future for these animals.

“This is a world-first conservation program that’s saving our endangered turtles and restoring an incredibly important ecosystem.

“Working with our project partners including the Wuthathi Nation and Meriam Nation (Ugar, Mer, Erub) Traditional Owners, we’ve already achieved a remarkable turnaround in the green turtle population.

“Because of the project, an additional 640,000 endangered green turtle hatchlings have already begun life on the Great Barrier Reef over the first four years.

“Saving the Reef and all its marine life including turtles is a huge task, but the success of the Raine Island Recovery Project shows that by bringing together science, business, government, reef managers and Traditional Owners, we can make an impact.

Theresa Fyffe, Great Barrier Reef Foundation Executive Director Projects and Partnerships

“The Raine Island Recovery Project has achieved real breakthroughs for marine conservation that will have genuine global impact. It’s a conservation world-first that has created a successful model and springboard for other reef-saving projects.

“Right now we’re taking what we’ve learned on Raine Island and establishing a network of climate change refuges by protecting other critical island habitats on four Great Barrier Reef islands.

Katharine Robertson, Department of Environment and Science, Queensland Parks and Wildlife – Senior Conservation Officer

“When we rescue an adult turtle and then see that turtle return to lay eggs is amazing. Knowing that I helped to save that turtle from dying and then seeing it back up on the beach nesting means that I have contributed to the future of the green turtle population which is just the most amazing feeling.

“Because of the Project and the support of the partners involved, each season we are going to see more and more hatchlings which will make a difference to the future of the northern Great Barrier Reef green turtle population.”

Traditional Owners travel to the island regularly to represent their people and support the teams carrying out sand testing, sand movement, turtle monitoring and satellite tracking. They instruct new teams through the turtle monitoring process and lead a lot of the special fencing, which has been used to prevent turtle deaths from cliff falls on the island.

Peter Wallis, a representative of the Wuthathi Nation Traditional Owners of Raine Island:

“My Grandmothers and Grandfathers, and many before them, used to go to this place, and for us, growing up in this modern world, it is pretty hard to get back to our history, so Raine Island is very important to us,”

“By being directly involved in the project and travelling to the island with the scientists, it gives our people a better understanding of how to best look after the island through science,”

“As an Indigenous nation, our involvement helps us learn from the scientists, but it is good for them too, to learn from the Traditional Owners.

“I think they get a better understanding of our respect for the country and that we are all the same. There is no black or white, it is just about respect for the land and respect for others, which is how we have been brought up.

“So I pretty much took it upon myself to try and get involved as much as I can with this sort of work.

“I can't explain the importance of it, growing up as a kid you want to be like your Elders.”

Jimmy Passi, a representative of the Meriam Nation (Ugar, Mer, Erub) Traditional Owners

“I grew up with land and sea back home, so it feels natural to visit here, but then we also use all the technology here so it is an awesome experience.

“I don't think there is any pressure because for us, it is like going home.

“Don't get me wrong, representing my people is really big because it can help keep our history alive.

“I really enjoy it and when I go home and tell my stories about the work and the island, it is having the effect of making other people in my community, younger ones, want to get involved too.”

Article By Great Barrier Reef Foundation

Photo Credit: Raine Island Recovery Project, Gary Cranitch, Great Barrier Reef Foundation, Christian-Miller

Want more conservation related articles?