Stuart Philpott explores the wreck of the M2 submarine, which was tragically lost with all hands in 1932 and now lies just 30m down in Lyme Bay.

I watched diesel fuel blob up onto the mirror-calm surface. The boat skipper said this was a good indication that we had found the dive site. Seeping from her ruptured tanks, the small circular slicks were a poignant reminder of what lay on the seabed below.

The M2 lies approximately five miles northwest off Portland Bill in Lyme Bay. This popular wreck is more than just a chunk of decaying metal. Her tragic story is steeped in disaster and despair. Protected by the Military Remains Act 1986, the experimental submarine has been designated as a war grave and should be treated with respect.

While gathering background information at the submarine museum in Gosport, I made a surprising discovery. Inside a glass cabinet full of relics was a small, insignificant piece of wood. Scrawled in pencil was the message ‘Help. M2 gone down. No 2 hatch open’. This had been found washed up on the beach at Hallsands in Devon after the M2 sank with the loss of all hands, the words more than likely written by somebody trapped inside the stricken submarine.

The sea has been my ‘office’ for the past 30 years, so I felt some kind of empathy with submariners and the dangers they face. But being trapped on the seabed with no hope of survival was not a thought I wanted to dwell on. Seeing this piece of wood had got me thinking more about the ‘human’ aspect, which entirely changed my perception of the wreck.

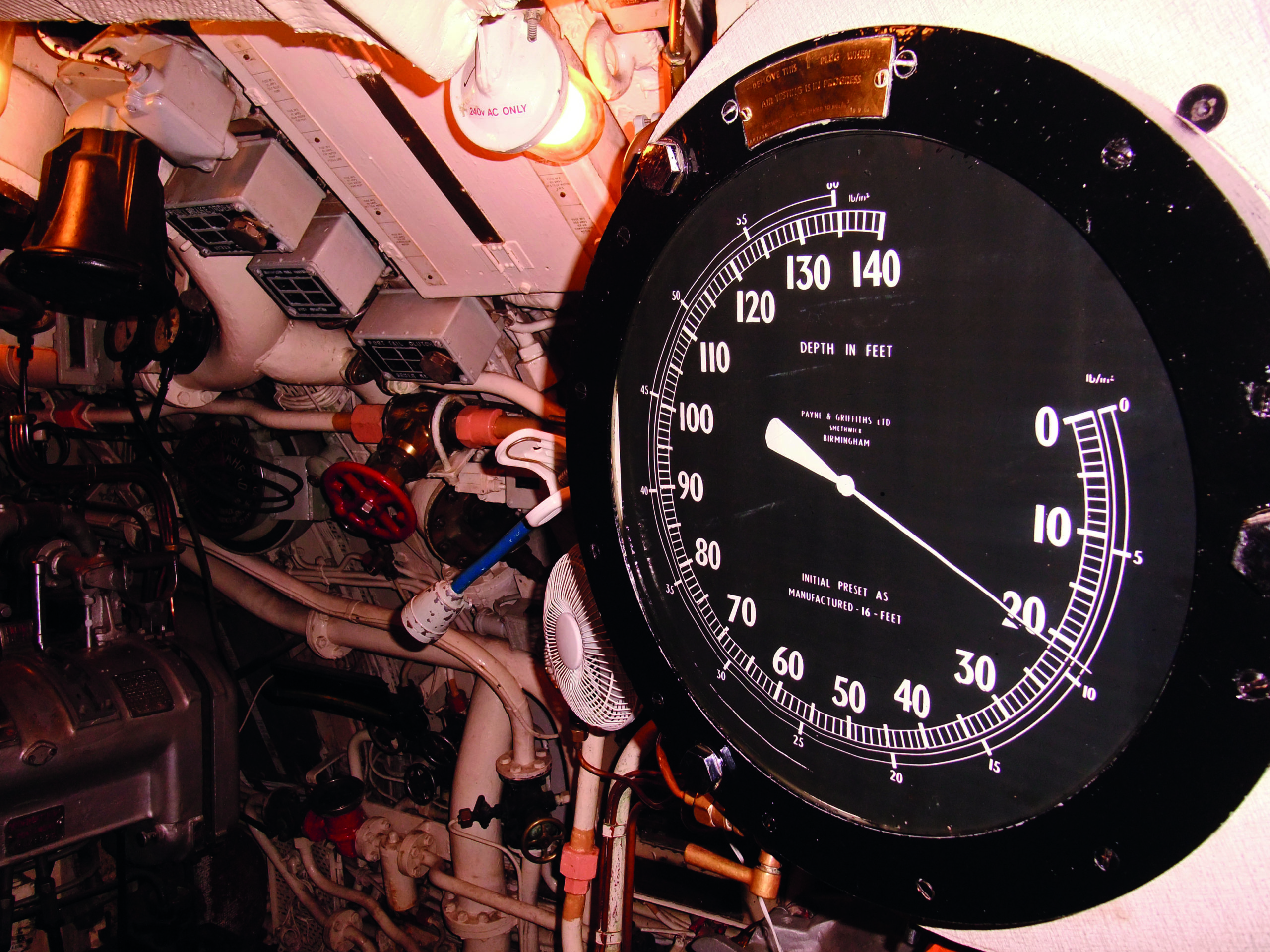

The 90-metre-long M2 submarine sits upright on a relatively flat seabed at a maximum depth of 31m around the bow and 35m at the stern. She is totally intact, apart from losing her twin three-bladed, 1.78-metre diameter propellers to salvage operators, and still looks like a proper submarine.

There are some visible signs of corrosion on the outer surface but otherwise the M2 is in pretty good shape considering her age.

I wanted to capture the wreck in all of its glory, but knew UK weather conditions were notoriously unpredictable. In past years, I have had pitch-black dives with less than an arm’s-length visibility and on better days up to four to five metres. To try and cover all possibilities, I made arrangements to dive over a series of three consecutive days in late-May. The long-range weather predictions and tidal flows looked favourable. I even added on an extra contingency day just to cover any unforeseen problems.

About M2 Submarine

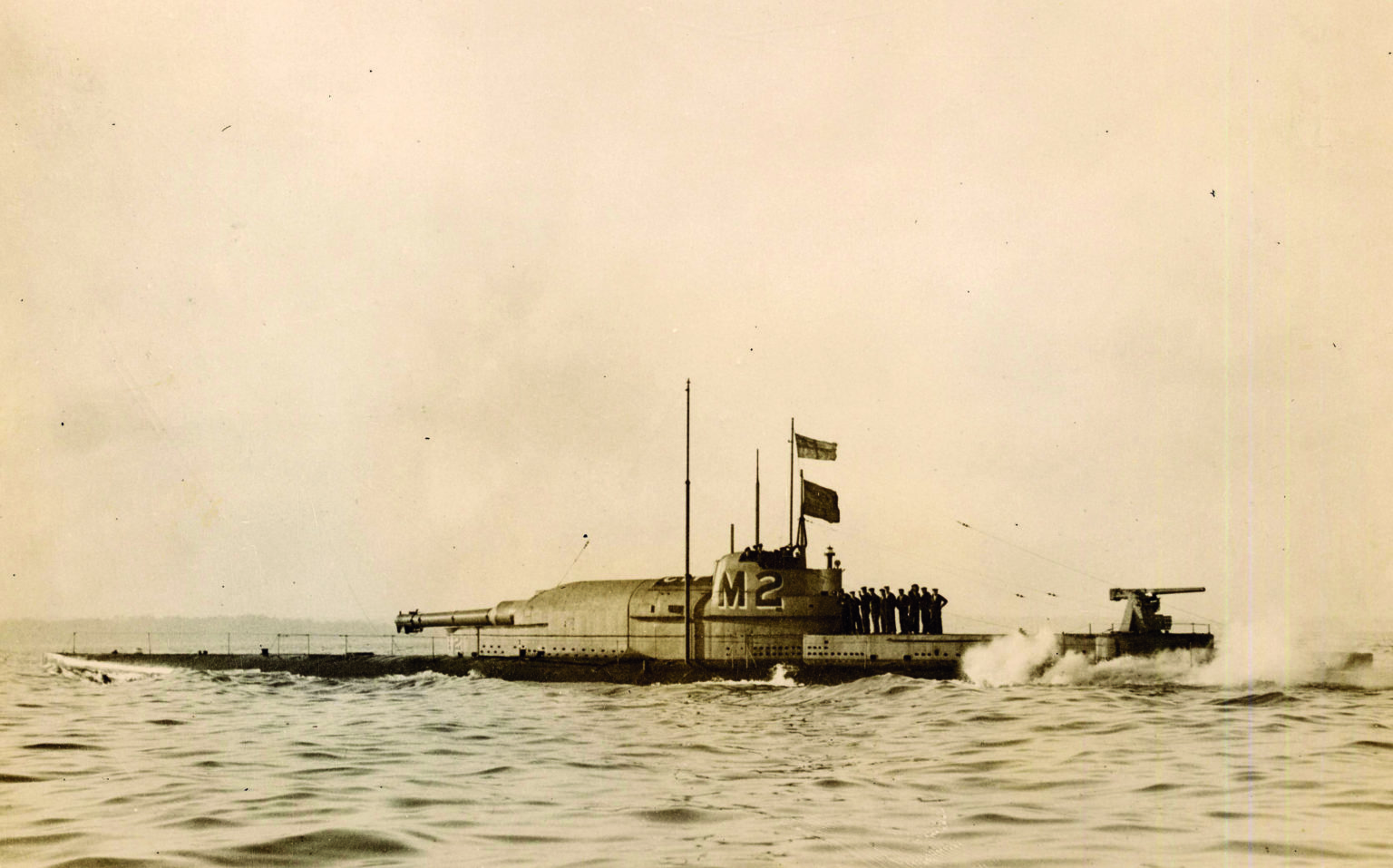

The M2 was one of four M-class submarines fitted with a battleship-sized 12-inch gun as main armament. The idea was to launch surprise attacks, i.e. locate the enemy, quickly surface, fire off a few rounds and then submerge.

The M2 was commissioned after the end of World War One on 14 February 1920. After four years of active service as a ‘test’ submarine, she was transferred to dry dock for a major refit. The Admiralty had devised an ingenious plan to turn her into the Navy’s first-ever Submarine Aircraft Carrier.

The conversion took three whole years to complete. Her big gun was removed and a special hangar built in front of the conning tower. This was large enough to house a custom-designed Parnall Peto seaplane.

The single-engine, two-seater biplane had folding wings (nine-metre wingspan) which allowed it to fit snugly inside the watertight compartment. Upon surfacing, the plane would be brought out from the hangar and positioned on a track in front of a compressed air-catapult system.

This gave the plane enough propulsion to ‘lift off’ from the foredeck. On landing, a crane fitted above the hangar entrance winched the aircraft back on board.

On 26 January 1932, the M2 was lost at sea during a training exercise. After an extensive search lasting eight days, she was located with her bow pointing towards the surface and her stern embedded on the seabed.

Salvage divers discovered that the hangar doors were wide open. While recovering the seaplane and two dead crew members, they also found that No.2 hatch located inside the hangar was not sealed shut. This led directly into the submarine and was undoubtedly the reason for her loss.

Orders were given to re-float the M2. All hatchways and openings were sealed off and compressed air pumped inside the hull. But after five failed attempts, they abandoned all hope of saving her. The submarine remained on the seabed with 58 bodies still inside.

Official records state that the crew were constantly practising drills to speed up operations. The record for surfacing to launching the seaplane had already been cut to less than ten minutes, but this time was always being beaten down.

The most-likely theory is that the hangar doors were prematurely opened while the submarine foredeck was still awash. Water would have poured through the doors and down the open hatchway, flooding out the submarine.

Whether or not all of the compartments were flooded at once is the $1,000 question. There could well have been survivors trapped inside.

There was a good mix of singles, twinsets and rebreathers stowed aboard as we left the jetty bound for the M2. Sea conditions were fair to marginal by the time we reached the Bill. If we had been on a RIB, the dive would have been cancelled by now (this had already happened to me on a number of occasions). I knew we were in for a bumpy ride when two members of the group threw up over the side. The weather stayed consistently poor throughout my whole three-day stint and only got slightly better on my final contingency day.

I had already worked out the underwater logistics. Sarah Payne had agreed to model for me and I had persuaded another friend to come along and point as many lamps as possible directly behind me into Sarah’s face. This way I didn’t have to totally rely on my camera strobes and would hopefully get a softer lighting effect on the subject as well as less backscatter.

Although this proved to be useful, it wasn’t nearly bright enough for the dark, snotty plankton-like conditions we encountered. I soldiered on for four days but the underwater conditions just weren’t ideal for photography. We planned our dive times for one hour surface-to-surface and this also took into account a few extra minutes of deco. Sarah and I were using an OC nitrox mix and my lighting assistant had brought along his Inspiration rebreather.

For the next few weeks I pondered over my images. Using photo-editing software, I could just about make them passable for publication, but they looked very gloomy and slightly out of focus. I didn’t expect Caribbean clear shots, but nonetheless in my mind they looked absolutely terrible.

I had already wasted four days of everybody’s valuable time but being the eternal optimist, I just had to give it one more try. I made arrangements for a return visit five weeks later at the end of July. Due to other work commitments, this would be my last opportunity of the year, so I better make it count!

Sarah looked quite anxious as we made our way out to the wreck site for a fifth and final time. The sun broke through the clouds and there was a slight swell but nothing too lumpy to contend with.

On the descent, I could see the shotline had been dropped on the portside of the conning tower. There were a few discarded ropes entwined around the superstructure but to my surprise I could see a reasonable proportion of the wreck. Comparing notes afterwards, Sarah and I guessed the visibility was an extremely rare ten metres, maybe more.

We finned past the dark, gaping hangar entrance and over the catapult towards the bow. Huge one-metre-long silvery pollock accompanied us down to the four 18-inch torpedo tubes (two on each side). Fortunately, there was no sign of any conger eels lurking inside.

I took a shot of the bow and this time could clearly see Sarah hovering next to both torpedo tubes. My fish-eye lens gave the straight lines a slight curvature, but I wasn’t complaining.

We ascended to the bow deck and doubled back to the catapult. The unusual shape was covered in little white cup corals and surrounded by a shoal of pouting. A big black conger eye appeared right below Sarah’s head as she was posed for me over the catapult track. I didn’t want to rattle Sarah and spoil my picture composition, so I just carried on taking pictures – sorry Sarah!

The conditions were such a contrast from my previous dives. I only had this one opportunity for pictures, so I made a decision not to stop at the hangar. This is the most-popular spot for divers to explore, which means it’s also the first place to get silted up.

I had ventured inside on a previous dive and the silt mound was piled high at the rear. The infamous No.2 hatch was well and truly buried underneath.

I briefly stopped to take some shots of two stubby pieces of metal protruding above the hangar, which turned out to be remnants of the crane, and then shot off towards what I think is the most-photogenic part of the wreck, the conning tower.

The M2 conning tower has a distinctive shape, with the rounded end being the front and the pointy end, with what looked like a jack staff (and a tompot blenny inside) attachment, at the rear.

I spent the next ten minutes taking pictures of the conning tower, periscope, snorkel and radio antennae with Sarah in the foreground. Unfortunately, we ran out of time before we had a chance to re-explore the stern, but as I had already clocked up 23 minutes of deco, I wasn’t about to complain.

Safely back on board, Sarah asked me the golden question ‘did I get any good pictures’? Although the composition and lighting looked fine on my small camera screen, I still couldn’t be 100 percent certain about the clarity until I downloaded the pictures.

But conditions couldn’t have been much better and I felt far more confident that this time we had done the submarine some justice. Looking at the finished results, I hope you agree!

I knew we were in for a bumpy ride when two members of the group threw up over the side

The M2 conning tower has a distinctive shape, with the rounded end being the front and the pointy end, with what looked like a jack staff (and a tompot blenny inside) attachment, at the rear.

Photographs by Stuart Philpott