Divers can make a huge difference contributing to citizen science programmes – with more Dive photos needed

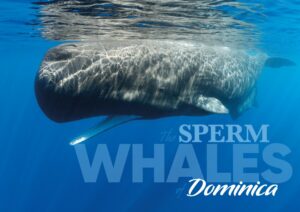

The travel restrictions brought around by the outbreak of coronavirus has left many divers landlocked and reminiscing over old dive photos and videos – remembering happier times spent underwater. Some divers may be fortunate enough to be looking at old footage of rare megafauna, such as manta rays or whale sharks.

If you are one of the lucky individuals with these photos, marine biologists are asking for your help to aid research and conservation projects for these gentle giants of the ocean.

Divers are being asked to submit old footage to online libraries such as Manta Matcher (for mantas) and Wildbook (for whale sharks).

Using computer software, researchers can then identify individuals through markings unique to each animal – for mantas, the belly markings differ between individuals. For whale sharks, the spot pattern on their whole bodies is different for each shark, and images of the area above the left pectoral fin enable the identification of individual sharks.

When the date, time, and location of the sighting is also uploaded, this simple action enables researchers to add to global databases of manta and whale shark sightings by identifying and tracking movements of individual animals – a powerful tool for population and migratory studies.

For years, such citizen science programmes around the world have been collecting data on mantas and whale sharks, leading to some surprising discoveries. However, with time on their hands now – and no doubt a backlog of photos and videos to sort through – divers have an opportunity to make a huge contribution.

Diver’s holiday photos and videos have already yielded remarkable insights into the behaviour and biology of megafauna.

One such example is the surprising tale of a whale shark sighted at Pulau Sipadan, in Sabah, in October 2019. Diver’s footage of the whale shark was uploaded onto social media, shared with researchers and identified on Wildbook. It turned out that the individual had first been sighted in Oslob in the Philippines – the first documented case of a whale shark moving between the Philippines and Malaysia using their spot patterns.

Gonzalo Araujo, an Associate Research Fellow at Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS), and Director of Large Marine Vertebrates Research Institute Philippines (LAMAVE) – based in the Philippines, enthused:

“The results highlight the need for divers to be involved in monitoring programmes particularly for endangered and enigmatic species such as the whale shark.”

“It would be fantastic for more photos and videos such as this one to enable more documentation of whale sharks or mantas around the world. Given the current global situation, it is an opportune time for divers to go through old footage and share it, helping research and conservation efforts globally.”

“Old footage would be particularly valuable, as it could give us not only a spatial reference for individual animals, but potentially a history of their movements too.”

Marine biology students at the UMS are taking advantage of the Movement Control Order in Malaysia to go through social media, tagging footage of whale sharks, and uploading to Wildbook – in the process, building a database of whale shark sightings in Malaysia.

“Whale sharks are at the top of many divers’ wish lists – understandably so, as it is the largest fish in the ocean, yet one threatened with extinction and increasingly rare to see,” said David McCann, Conservation Manager for S.E.A.S (Sea Education Awareness Sabah), based at the dive operator Scuba Junike Mabul Beach Resort.

“We have been sending identification images of whale sharks for years to the Wildbook database, but the recent Covid-19 situation has enabled us to go back through old footage and tag whale sharks there.”

“We had a huge backlog”, he laughed, “with thousands of dives at sites in the Semporna region, including Sipadan, Mabul, Kapalai and the islands of the Tun Sakaran Marine Park. We also went through footage taken in Kota Belud, near Kota Kinabalu.”

“It was quite a fun task, almost like a giant logbook of sightings – and it brought back many fond memories. We look forward to the end of travel restrictions, when we can get back into the water and take new photos!”

McCann concluded, “As divers, we enjoy the beauty of the underwater world – now more than ever we realise how much we miss it. It is only right that we seek to protect and aid it in any way possible assisting research and conservation through citizen science is a simple – yet effective – step to take.”

Photo Credit: Gonzalo Araujo

For more information about Sabah visit Sabah Tourism

Want to read more conservation articles?