Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there, wondering, fearing, doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before – Edgar Allan Poe.

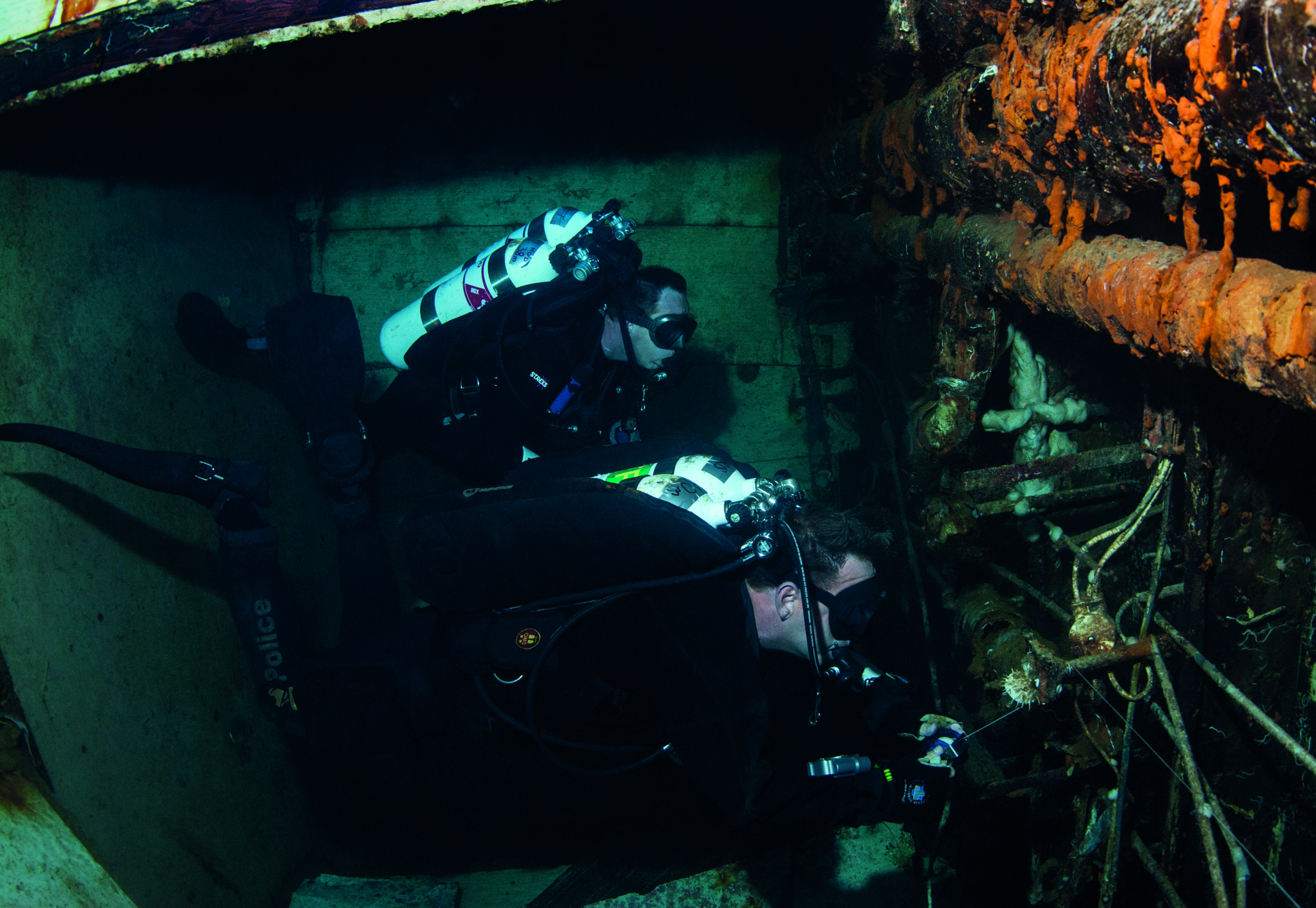

“Congratulations, you’ve just killed everyone,” said Chris Demetriou, the Ops Manager at Dive-In Larnaca, based in Cyprus. We had ventured deep inside the MS Zenobia wreck and, sure enough, the dive hadn’t gone as planned, but where had I made such a fatal mistake? This had been my penultimate dive on the TDI Advanced Wreck Diver course. The past three days had been more psychologically demanding than I had ever imagined.

Chris said: “I don’t have to load the course with simulated problems, they just happen in real time.” He was dead right – pitch black, encased in claustrophobia-inducing metal, without any lights or guidelines; situations could get quite interesting, if not extremely tense!

The Zen is an ideal wreck for technical diver training. On 7 June 1980, the 165-metre-long, 10,000-ton, roll-on, roll-off ferry sank in the middle of Larnaca Bay. She now lies on her port side at a maximum depth of 42m. Her demise has long been steeped in controversy and intrigue. The most-plausible theory is she sank due to a malfunction with the computerised system controlling her ballast tanks. There have never been any salvage operations.

A full cargo of 104 articulated lorries and heavy plant machinery still lie chained to the decks and stacked inside her holds. This popular dive site is conveniently located just a few minute’s RIB ride from the harbour.

Chris has spent a number of years developing the course itinerary. Most of the training dives are conducted inside the officer’s day room and the captain’s bedroom. The two rooms are totally enclosed, with some daylight filtering down from a row of rectangular windows above. Chris explained: “You don’t need to go deep inside for the course.” Just to confuse matters, the Zen lies on her port side so doorways, walls, ceilings and windows are not where they are expected to be. Chris said: “When planning any penetration dives, it’s vitally important to consider room orientation and the overall wreck layout.”

Although there are some theory sessions, most of the four-day course focuses on practical exercises. Ex-Londoner Chris said: “This is my favourite TDI course; we’ve already run about ten this year.” He usually limits numbers to two divers per course. Minimum certification requirements are PADI Advanced Open Water Diver with the Wreck Specialty and 50 logged dives, or any certifying agency with a wreck familiarisation certificate and the prescribed number of dives. Divers really have to be in the right mindset for this course. Chris said: “We don’t have to fail anybody, they end up failing themselves.” He continued: “This course is not for ‘badge collectors’. By the end of the second day, I know if they are going to make it or not.”

My first dive was basically an orientation. This gave me a chance to get familiar with the wreck’s key features and my own equipment configuration. I had been partnered with Scott Ayrey, an experienced trimix diver. All participants have to be geared up with twinsets and a stage cylinder. Chris prefers to keep his kit as streamlined and as basic as possible – “I don’t want to look like a Christmas tree diver,” he says.

There are no cages covering his manifolds, or rubber boots and nets on the cylinders. Chris said: “It all ends up snagging on the wreck.” Chris guided us to the bulkhead door that led into the officers day room. We checked depth, time and cylinder pressures before entering. Our first task was to sketch a map of the entrance and highlight any distinguishing features inside the room. This included piping ducts, windows, carpet, wiring, hatchways, etc. Over the next few dives, Scott and I would become very familiar with the layout.

There was definitely no time for sight-seeing. Taskmaster Chris got us doing a number of gas isolation exercises simulating a fractured manifold or a dislodged regulator. A catastrophic gas leak in an enclosed, overhead environment is a real threat. Chris showed us what to do and then it was just a case of following the procedure step by step in a calm, co-ordinated manner. All of the skills were performed at around 25m.

On the ascent I switched over to my 50 percent O2 stage cylinder. Gas-switching computers make decompression management a whole lot easier. Permanent marker buoys have been placed at the stern, amidships and bow of the Zen, and there is even a trapeze set up at 5m to make deco stops more comfortable. Chris was still piling on the pressure. We stopped and practiced deploying our delayed SMBs, which turned out to be quite eventful when someone – who shall remain nameless – forgot to tie the reel line to the SMB!

Subsequent dives mainly focused on lost mask procedures, laying/retrieving a guideline and using Scott’s long hose in an out-of-air scenario. I spent the first few moments of each exercise gaining composure and thinking about logistics, i.e. make sure the long hose is free of any restrictions when air sharing and remembering to keep the line placement as simple and snag free as possible before reacting to the task. The course also taught me the importance of carrying a back-up mask and at least two cutting devices. As Chris had said: “It’s the simple things that are life saving.”

Dive four turned out to be the toughest of them all. I had to wear Chris’s special blacked-out (leaky) mask and find my way out of the officers day room by feel alone. It was similar to playing the popular party game ‘put the tail on the donkey’, but on a grander and much more serious scale.

Chris spun me around and moved me up and down so I was totally disorientated. There was no guideline this time, so I would have to rely on my memory of the room layout and try and find a familiar object to use as a reference point. My whole sense of perception was left in a severe state of chaos and confusion.

This was quite a scary moment, even though I knew Chris was there with me watching my every move. My gut feeling was to ascend a few metres until I bumped my head on the windows and then move across to a corner where I would hopefully find the carpet. Eventually, after ten minutes of fumbling about, my fingertips felt the familiar texture of woollen fibres. What a relief – I knew this would lead to the bulkhead door and eventual freedom.

Chris said that the record for escaping the room was two to three minutes, but some divers had taken more than an hour to find their way out. I’m not sure I would be able to keep my nerve for that long!

Our last day involved planning and implementing two relatively ‘simple’ wreck penetration dives. Scott and I entered through the bridge and took it in turns to lay a line from the laundry room through to the upper car deck. On the way out, we had to simulate an out-of-air and a ‘light out’ exercise. Chris told us we should always carry a primary light and two back-ups in case of any failure. As I had already discovered on ‘buttock clenching’ dive four, not being able to see inside a wreck is a nightmare scenario.

Scott was first to lay a guideline. I always thought there would be plenty of pipes, hinges and handles to wrap the line around, but it wasn’t that easy. Chris said that on a previous course one of the participants had wrapped the line around a floating plastic sheet. This was obviously not a good tie-off point for a guideline! Chris had already taught us about snoopy loops, line arrows and suitable tie offs, so we were completely clued up and raring to go.

On the return journey I was leading the way while simulating out of air using Scott’s long hose. We were in single file moving along a narrow passageway. It was absolutely pitch black so I slowly and methodically ran my fingers along ten metres of nylon line back to the primary tie-off point. Along the way we had to negotiate a tight hatchway and go up and over a doorway.

If I moved too fast, Scott’s regulator would have been pulled from my mouth and if I had let go of the guideline, I would be totally lost. I was 100 percent dependent on Scott and really didn’t like this feeling of reliance. We eventually got back to our entry point and successfully completed the training exercise.

We then reversed the roles and went through a second time. This is where my lack of experience laying guidelines really taught me a lesson. There was already a guideline inside the wreck leading off into a different room. Chris said he had often been inside wrecks where other divers had left discarded lines.

By mistake, I put my primary tie off on the existing line and reeled in from this point. I put directional arrows on the line to show the way out, but placed my arrow on the wrong line. This meant we would have got completely lost inside the wreck. Chris said: “You won’t make that mistake again.” He was right, and this was by far the best way to learn – under controlled conditions. The more problems I encountered on the course meant I would be more capable of dealing with them in real life. The TDI Advanced Wreck Diver course had given me a whole different perspective to playing around in the dark.

Although it had been a tough four days, I had enjoyed every moment. We had started off with the basics and worked our way up to some heavy task-loading exercises. Chris made sure we had a thorough de-briefing after each dive. This gave us a chance to sit down and discuss any problems and go through remedial actions.

I soon realised that it was essential to keep a cool head. It also pushed home the fact that my buddy had to be just as level-headed. I was lucky to have Scott as my training partner. All I can say is choose wisely. Chris said: “Panic will kill you all day long. The key is to never give up.” I had performed all of the skills in a ‘controlled’ environment and Chris was always close at hand if any real problems had occurred.

Although I satisfactorily completed all the training exercises I still couldn’t stop thinking how would I react in a real life-or-death situation? Pitch black, deep inside a wreck with no guidelines, no buddy and no visible exit – what would I do?

Permanent marker buoys have been placed at the stern, amidships and bow of the Zen, and there is even a trapeze set up at 5m to make deco stops more comfortable

By mistake, I put my primary tie off on the existing line and reeled in from this point. I put directional arrows on the line to show the way out, but placed my arrow on the wrong line. This meant we would have got completely lost inside the wreck

TDI Advanced Wreck Diver course: - Course duration: Four days Number of dives: Six Zenobia wreck dives Participants: Two per course Cost: 625 Euro (Includes boat fees, tuition, gas and cylinders. Manual and certification are an extra 84 euro). Kit hire is not included.

Photographs by Stuart Philpott